One day, you’ll appreciate drinking recycled toilet water.

Urban populations are growing as water supplies are dwindling, often due to worsening droughts. In response, some communities are treating wastewater, rendering it perfectly safe for consumption. It is so pure, in fact, that if a treatment facility doesn’t add enough of the minerals the filtering process strips out, it could do serious damage to the human body. And trust me — it tastes great, too.

Cities throughout the American West are already recycling water, easing pressures on dwindling supplies. Now here’s a thought experiment: How much would you pay on your utility bill for the privilege of reused water, if it meant avoiding shortages and rationing in the future? A recent survey offers one answer. Residents of small communities of fewer than 10,000 people said they’d be willing to drop an average of $49 to do so. That money would underwrite water reuse programs, including rain capture systems. “I do think it is a bipartisan issue,” said Todd Guilfoos, an economist at the University of Rhode Island and co-author of the new paper. “It’s often just cheaper than some of the other available solutions.”

Wastewater recycling is not some far-out, prohibitively complicated technology. Western states are already doing a lot of it: A study published last year found that Nevada reuses 85 percent of its water, and Arizona 52 percent. Water agencies do this with reverse osmosis, passing the liquid through fine membranes to filter out solids before blasting it with UV light, which destroys any microbes. On a smaller scale, apartment buildings can house their own treatment infrastructure, cycling water back into units for nonpotable use, like flushing toilets.

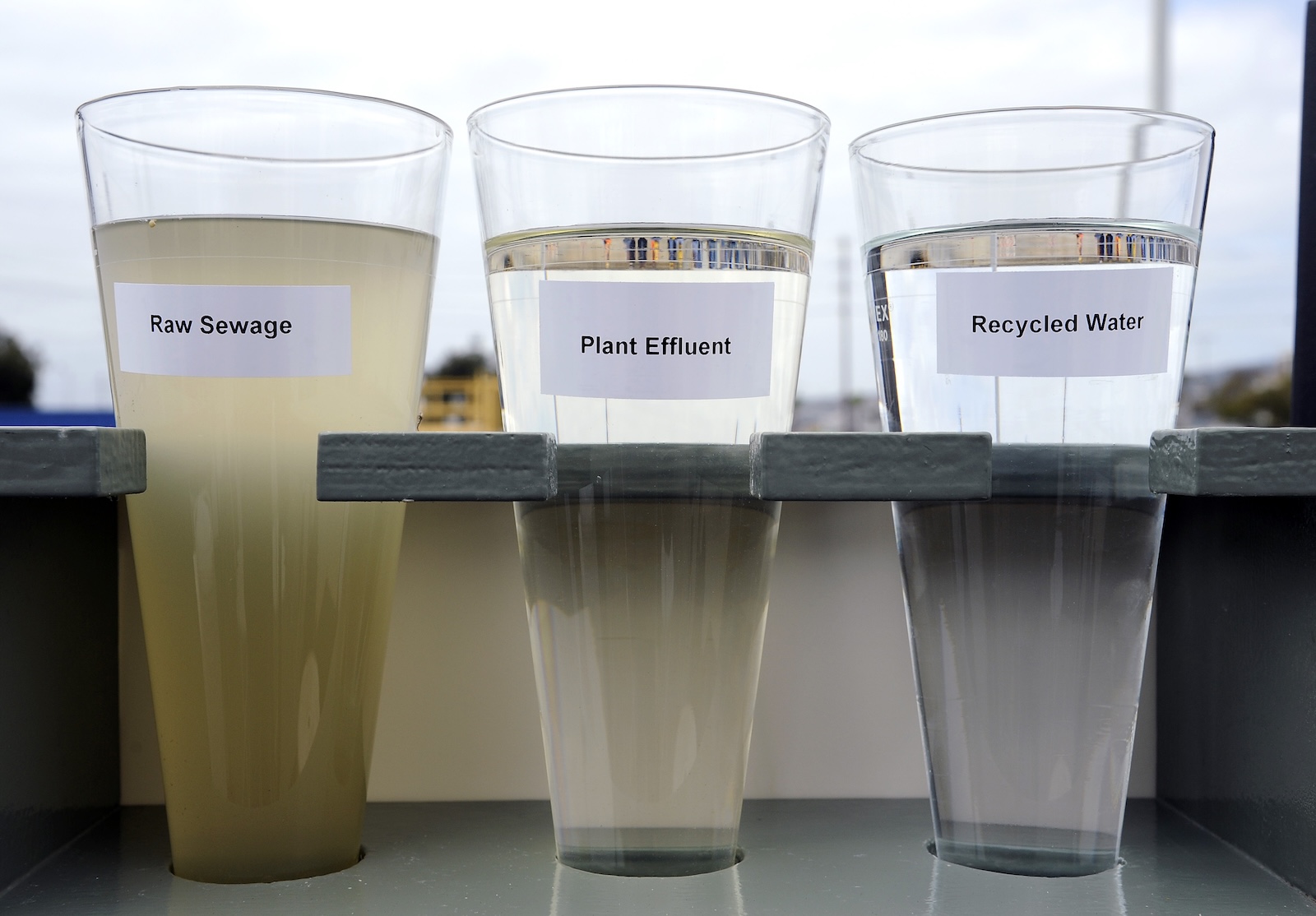

Glasses containing raw sewage, plant effluent filtered, and recycled water are displayed at an advanced water purification facility in 2015 in Los Angeles, California.

Bob Riha, Jr. / Getty Images

On the municipal level, though, it’s expensive to build such facilities and run them continuously — it takes a lot of energy, for instance, to force water through those membranes. For a small community, charging each household $49 per month wouldn’t be quite enough to get a system up and running. “While that might be enough for operating, that doesn’t include what it would cost to actually build whatever water reuse infrastructure that you would need,” Guilfoos said. That’s when a town can turn to federal or state grants, or maybe utilize municipal bonds, to break ground. “I think communities need a little bit of a bump, actually, to get there,” Guilfoos added. “I think usually it’s in the face of some crises that these things end up getting built.”

Those crises are piling up across the U.S. Droughts are forcing some rural areas to pump more and more H2O from aquifers, depleting them. Tapped unsustainably, these underground supplies can collapse like an empty water bottle, making the land above sink, a phenomenon known as subsidence. This is a particularly pernicious problem in agricultural regions — California’s San Joaquin Valley has sunk up to 28 feet in recent decades, to offer just one example.

If supplies dwindle, a small community would have no choice but to ration water. Getting more efficient about using what we have can help, like encouraging the adoption of thriftier toilets and spraying less on lawns, as Las Vegas has done. (Those thirsty patches of green are in general an environmental mess, beyond their use of water.) But to truly get more sustainable, a community will have to recycle the H2O it has no choice but to use.

Read Next

Los Angeles just showed how spongy a city can be

What’s interesting about this study, says Michael Kiparsky, director of the Wheeler Water Institute at the University of California, Berkeley, is the apparent overcoming of the “yuck factor.” “There’s a visceral reaction to drinking reused water, particularly reused wastewater, that’s totally understandable,” said Kiparsky, who wasn’t involved in the research. “But over time, that has faded as the notion of reusing water to augment water supplies, including for drinking water, has become increasingly legitimized.”

At the same time, simple infrastructural improvements can capture heaps of another supply that’s readily wasted: rain. That $49 a month could fund bioswales, for instance — ditches full of vegetation that not only collect stormwater, but provide habitat for native plants and pollinators. Cities like Los Angeles are making themselves more “spongy” in this way, with roadside plots of land that collect runoff in subterranean tanks. Elsewhere, architects are building “agrihoods” around working farms that store precipitation to hydrate their crops through the summer.

In the American West, farmers are also having to contend with water whiplash, meaning years of plenty followed by years of desiccation. Generally speaking, rain is falling more heavily because a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, increasing the bounty. But so too does climate change exacerbate droughts, making wastewater reuse especially welcome on farms. “All of this makes the water supply less certain in any given year, and more volatile from year to year,” said Tom Corringham, a research economist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, who wasn’t involved in the new paper. “So any strategies that we can find that can smooth out the water cycle are beneficial.”

In addition to recycling wastewater, farmers are recharging the aquifers beneath their feet: When rains fall heavily, and there’s a surplus of water, channels divert fluid into “spreading grounds” — basically big dirt bowls built into the landscape. That allows precipitation to percolate back into the ground, reducing loss from evaporation, replacing what’s been drawn out, and helping avoid land subsidence. Then, when needed, a farm can pump the water back out of the ground, in which case it doesn’t need to draw from, say, a dam, leaving more water for others to use.

Together with wastewater reuse, aquifer recharge can help bolster the water system for the climatically perilous years ahead. As metropolises like Mexico City and Cape Town run the risk of running out of water, drinking recycled wastewater will be a whole lot more appealing than losing hydration entirely.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Would you pay $49 a month to drink recycled wastewater? on Feb 20, 2026.

From Grist via This RSS Feed.

What do people normally pay there? I pay €15 a month for water.