The U.S. food system operates a lot like fast fashion, say Liz Carlisle and Aubrey Streit Krug. In their new book, Living Roots: The Promise of Perennial Foods, they explain that most crops—like the corn, wheat, rice, and soybeans that dominate the system—are annuals, in the ground for a single season. They are harvested by people working in less-than-ideal conditions; processed into cheap, low-quality products; and shipped out in high volume. All the while, their supply chains expend a tremendous amount of fossil fuels.

With the changing climate front of mind, Living Roots explores an alternate vision, one focused on the long game and built on perennials—plants that remain in the ground year after year. Edited by Carlisle and Streit Krug, the collection of 34 essays by Indigenous leaders, farmers, scientists, and chefs makes a case for centering perennial crops on our farms and in our diets.

Because of their deep and robust root systems, perennial crops—including fruit and nut trees, forage grasses, and grains like Kernza—can pull large amounts of carbon out of the atmosphere and store it underground. They also reduce erosion, increase the organic matter in soil, boost biodiversity, and improve the health of those who eat them.

Because of their deep and robust root systems, perennial crops can pull large amounts of carbon out of the atmosphere and store it underground.

In the book, we hear from Indigenous people restoring buffalo herds on the native grasslands of the Cheyenne River Reservation in South Dakota and studying the sacred serviceberry on Blackfeet land in Montana. We hear from the creators of an urban food forest in Southeast Atlanta and a farmer raising chickens under a protective canopy of hazelnut trees in Minnesota. And we meet the researchers studying the ecological effects of prairie strips, or perennial patches within annual crop fields, and those developing perennial versions of rice, sorghum, and the oilseed silphium.

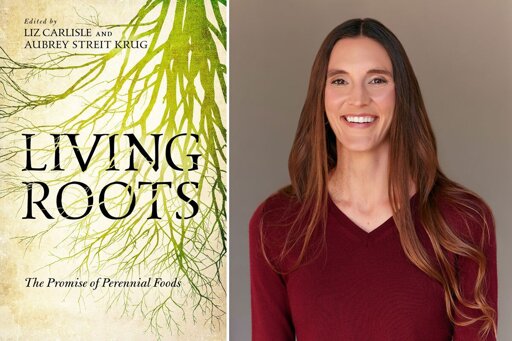

Recently, we caught up withCarlisle, an agroecologist and associate professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, to discuss the promise of perennial agriculture, the roadblocks it faces, and where she finds hope.

A number of your books, including Lentil Underground, Grain by Grain, and Healing Grounds, have looked at the promise of organic and regenerative agricultural systems. How does this book fit into your trajectory as a writer and thinker, and what do you hope it adds to your body of work?

Working on this project has been about trying to respond to this moment. I’m feeling the weight of so many crises at once. There’s the urgent need to slow emissions but also the urgent need to adapt to the climate change that’s already here—and then at the same time, the urgent need to address the deep divisions and inequity in our society that are making it difficult to tackle collective challenges like climate change. I see the perennial movement as having the capacity to help us do all these things at once.

How did you select the contributors to the book?

Groups that have been working hard for a long time—on things like agroforestry or regenerative grazing or breeding perennial grains—are starting to come together into a broader perennial movement. We wanted the book to offer a behind-the-scenes. What would it be like to host an awesome potluck with all these people working on perennials in different ways?

We wanted the book to represent different kinds of perennial foods and their diverse geographies, mostly across North America but a little bit from around the world. We also wanted to show the diverse roles that people play.

Do you have personal experience with the perennial movement, or are you approaching it more from the perspective of an interested researcher?

It comes from a personal place for me, and for Aubrey as well. For me, the joy of participating in the culture around perennial foods—whether it’s planting fruit trees in a community orchard or enjoying the culinary traditions from all over the world that are tied to them—reminds me what a beautiful planet we live on, and how joyful it is to live in community. It helps me get up every day and fight for those things, and it propels me forward to do my larger work as a researcher and an educator.

Also, one of the most exciting things for me is experiencing what a powerful rallying point perennials are for people from different parts of the political spectrum. When you start talking about planting a tree to benefit future generations, that’s something a lot of people can get behind, together.

The environmental benefits of perennial agriculture are well documented, and yet 60 to 80 percent of cropland is dedicated to annuals. Why has getting farmers to adopt perennials proven so difficult?

Many of the book’s contributors have written about this in their own context. I think about Wendy Johnson, an amazing Iowa farmer. She talks a lot about how crop insurance is such a huge impediment for folks in the Midwest to move to anything other than corn and soy, let alone perennials. So that’s about current federal farm policy.

There’s also the way markets are structured—do farmers have a clear opportunity to sell that crop into a market they can count on?

In California, land tenure is a big issue. When folks are renting on short-term leases—one, two, or three years—they can’t really plant perennials and be there for those perennials to benefit them.

What are the biggest challenges for the perennial movement under the present administration?

Climate Smart Commodities funding [canceled in April 2025] had been a huge boost to perennials, better than anything we’d ever seen from federal farm policy.

Jesse Smith, my neighbor here in Santa Barbara, is the leader of an elderberry project that involved a bunch of partners across coastal California to develop native blue elderberry as a viable commercial crop. When they lost their Climate-Smart Commodities funding and had to jump through hoops to try to get it back, that slowed what had been exciting progress, not only on the farm, but with things like a processing facility, which is key to make a viable market. Losing that funding was a big blow.

The other challenge: A transition to perennials is a huge learning experience. People need to figure out what to grow, which varieties, how to space them, and how to take care of them over multiple years. The pullback of USDA staff that would have supported farmers in transitioning to perennials has been a real challenge.

Is there a flip side—are there unique opportunities now?

What’s happening on the community level, with the growth of organizations like the Savanna Institute and movements like Indigenous buffalo restoration, is just extraordinary.

There’s a lot more knowledge and resources in the community for farmers who are looking to perennialize. They have a better chance of finding a peer who could be a mentor or finding a conference that they could attend to support them in that transition.

Also, the transition to perennials or more regenerative methods in general might have felt voluntary or opt-in 20 or 30 years ago. Now, a lot of farmers and farm communities are experiencing just how difficult it is to continue with conventional farming under the current climate and market circumstances. The chaos is driving a lot of people to look for alternatives. And there are robust community efforts waiting to receive them.

Many contributors identify with perennials on a very personal level, and several speak to their spiritual significance. What makes perennials resonate in this deep way?

Perennial plants weave these intergenerational connections—you can literally find yourself pruning a plant that a parent or a grandparent pruned, and you can see the evidence of their care. You might even connect to an ancestor you didn’t even know when they were living, but that plant is a connection between you.

Plants, like people, have to make decisions about how to allocate resources, and perennial plants make this interesting choice to allocate a large share of the energy they harvest from the sun to building up robust root systems. These roots support a whole community of organisms underground, providing a profound lesson about getting through hard times by investing in community and collective wellbeing.

Wisconsin agriculture educator Laura Paine points out that annual cropping systems are always a carbon source, not a carbon sink, and even using regenerative techniques on annuals cannot be considered a solution to climate change. What do you make of Paine’s point, and are perennials the only climate solution?

She’s in this Midwestern context, and has seen a lot of attempts to take really simplified agroecosystems—corn and soy monocultures—and add a single ecological practice to try to solve the problems associated with them, whether that’s no-till or a small amount of cover cropping. I think it has been frustrating for her to see the inadequacy of that response.

Combinations have been more effective, and perennials bring a combination, because if you’re growing perennials, you’re not tilling as much—maybe not at all—and you have roots in the ground all year round. We’re certainly not suggesting that agriculture should be only perennial, but it’s essential that we move towards more of a perennial balance.

In his essay, Ted Crews of The Land Institute points out that perennializing agriculture could be an ecological and social game changer, but the existential threats of climate change, biodiversity loss, and food security require faster solutions. What do you see as the way through?

At this point in the climate crisis, we have to find ways to address short-term problems that also contribute to long-term solutions. What I see in the perennial movement are some immediate solutions for farmers looking for alternative crops and for communities looking for local, healthy food sources. At the same time, [by growing these,] we’re building towards better climate resilience and lower emissions for the future. We really do need to do both things at once.

We don’t have to wait on the perfect Kernza variety. We have many perennial foods that we can work with right now as we’re developing those crops. Folks at the Savanna Institute are working to make hazelnuts better for farmers, but we can be planting them and processing them and eating them right now, even as we improve those varieties.

Wendy Johnson started with an acre of chestnuts and apples on her family farm. Now she’s directly managing a little over 100 acres, and she helps her dad with 1,000 acres, still mostly conventional corn and soy. They’re not in a financial place to just overnight convert the whole thing [to perennials], but she’s weaving them in, knowing that 30 years from now, that will better set up the next generation to make it a viable operation.

What surprised you most as you collected these meditations on perennials? What new insights or understanding emerged?

The long-game aspect of it was maybe one of the biggest lessons for me. A lot of stories have multiple turns in them. Like Wendy Johnson, growing up on a farm in Iowa, moving away to LA for a career in fashion, and getting inspired to go back and convert some of the farm to organic. A story could end there, but hers doesn’t. Her organic corn and soy plants get flooded out twice [in 2016 and 2018], and so she has another aha moment—‘Maybe I need to move to a more perennial cropping system.’ And then, she talks about the challenge of building it out in the current environment.

A surprise for me, and a gift of this book, is thinking about change at the pace of perennials. If you want to have fruit at some point, you got to plant that tree and take care of it. That’s what impresses me most about the folks in this book—their ability to engage in deep, long-term processes.

If someone reads this book and wants to support the adoption of perennials, what would you encourage them to do?

Plug in with a community of people, whether it’s working on an urban food forest, like the incredible one in Atlanta that Kelsi Bowens and Rosemary Griffin write about, or helping farmers establish hedgerows, or working in a community garden.

And then, of course, we have to change the policies and the structures that our farmers work within. Let lawmakers at all levels know that [perennial agriculture] is important and that you want to see investment in it. We certainly have a lot of opportunities at the state level right now. California and some other places like Minnesota are moving things forward with incentive programs for farmers that help pay for establishing perennials. And there are also some equally exciting programs at municipal and county levels, including with urban orchards.

Within the perennial movement, where are you seeing the most promise and hope right now?

During the pandemic, there was this huge upswell of energy around community food systems—mutual aid groups and urban food forests—and I’ve seen a lot of that sustained. That’s a bright light.

I’m also really excited about regenerative grazing and how that’s taking off within communities involved in animal agriculture. I’m headed to the perennial farm gathering that the Savanna Institute sponsors in March, and it’s been super exciting to see that get bigger and bigger as folks get excited about agroforestry.

There are a lot of points that are individually exciting, but then you put them together and you’re like, ‘Wow—this is a lot of roots going in the ground.’

This conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The post The Power of Perennial Agriculture appeared first on Civil Eats.

From Civil Eats via This RSS Feed.