The Twenty-Third Art Bulletin (January 2026)

![]()

Listen to ‘March for the Beloved’(임을 위한 행진곡), written in 1981 by activist lyricist Paik Ki-wan.

Leaving behind no love nor honour, not even names

Only a burning oath sworn to the end of our lives.

Comrades are gone, but our flag alone still flies.

Let us not tremble until the new day arrives.

Years pass, but the land remembers

That heated cry of awakening:

As we lead the way, let the living follow!– ‘March for the Beloved’(임을 위한 행진곡, 1981)

On 1 November 2025, protesters gathered across South Korea and chanted ‘No King: Trump is not welcome!’. These rallies were organised in response to the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) meeting in Gyeongju, which took place from 31 October to 1 November. On the sidelines of this meeting, Donald Trump confirmed that he would impose tariffs on South Korea that would result in the extortion of $350 billion, a plan that he had announced earlier that year. This was yet another example of his administration’s ‘America First’ agenda which subordinates the sovereignty of nations across the world, but particularly in the Global South. As the APEC meeting took place in Gyeongju, hundreds gathered nearby at the People’s Summit to read and sign the Gyeongju People’s Declaration, a statement calling for an economy for all, not just for the few.

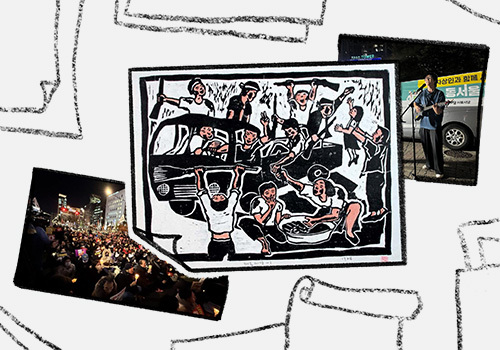

![]()

Hong Song-dam, May-27 Daedong Sesang (A World of Great Unity), 1984.

Before the summit began, the crowd took a moment of silence to pay their respects to the martyrs killed during the 1980 Gwangju Uprising, a student-led protest against the military rule of Chun Doo-hwan (1980–1988) that ended in a violent massacre, and then sang ‘March for the Beloved’. Written in 1981 by activist lyricist Paik Ki-wan to honour those massacred in the Gwangju Uprising the year before, the song has become an anthem of Korean social movements. This practice of honouring martyrs by singing together, an example of minjung-uirye (민중의례, or ‘pledge of the people’), began as a conscious refusal by South Korean activists to pledge allegiance to the national flag during Chun’s military dictatorship.

During my time in Korea for the People’s Summit, I sought to understand the role of a similar tradition, minjung-gayo (민중가요, ‘people’s songs’), in Korean political movements today.This genreof Korean protest musicemerged during the struggles against the military dictatorships that ruled South Korea from 1961 to 1988, before and during Chun’s regime, and continues to be used by social movements today.

This bulletin draws from conversations I had with members of art collectives like Maru (마루), which performed at the summit rally, and the recently formed feminist singing group norae-pae I-eum (이음, ‘connection’ or ‘bonding’), a part of the Seoul Women’s Association (서울여성회) that fights for gender equality. What emerged through my conversations was a picture of the living radical tradition of minjung-gayo undergoing a quiet revival and even intersecting in new ways with gender and with the heavily commercialised K-pop industry to advance the people’s message today.

A People’s Music Against Dictatorship and for Reunification

![]()

A mobilisation during the People’s Summit in Gyeongju, where protestors sang ‘March of the Beloved’ (right).

Minjung-gayo distinguishes songs created for and by the people from daejung-gayo (대중가요), or mainstream popular music. During the military dictatorship era, creating minjung-gayo was dangerous. In 1971, for instance, the military junta banned pioneer Kim Min-gi’s (김민기) song ‘Morning Dew’(아침 이슬). Yet people found ways to access the song, and it became one of the most beloved anthems of the democratisation movement which continues to be played at protests today.

According to the Maru collective’s Kang Hyo-jun (강효준), though minjung-gayo had already emerged as a genre, it ‘boomed’ after the Great Workers’ Struggle of 1987, when over three million workers launched strikes that finally forced democratic reforms in South Korea. ‘A lot of new songs were being written [during this time]’, Kang explained.

For many in the minjung movement of the 1970s and 1980s, the struggle for democracy was inseparable from long-standing demands for national reunification and liberation, from the partition of Korea in 1945 to the devastation caused by the imperialist Korean War that began in the 1950s and the permanent presence that the US established in South Korea in 1957. Songs like ‘Our Wish Is Reunification’(우리의 소원), which was originally composed by Ahn Byung-won in 1947 with lyrics by his father, Ahn Suk-ju, gave voice to the longing for the reunification of Korea. Other songs drew on Indigenous musical traditions such as pansori (판소리), a genre of musical storytelling, and gut (굿) shamanic rhythms, reclaiming cultural traditions that had survived colonisation and mobilising them as resources for contemporary struggles.

Very few new songs have been written in recent decades, however, a trend that mirrors the weakening of South Korea’s progressive movement itself. ‘The people’s art movement could not help but follow that decline’, Kang reflected. Collectives such as Maru work to keep the tradition of minjung-gayo alive: as Kang told me, ‘we must… keep writing new songs, expand our solidarity, and listen to the people’s stories to turn those stories into even more new songs’. Maru’s vision aims to broaden their social movement base through music that represents people’s struggles today. ‘When a revolutionary moment comes and when a new world comes,’ he expressed, ‘it will be our songs that will be sung’.

Similarly, the Seoul Women’s Association’s singing group norae-pae I-eum seeks to create minjung-gayo that are representative of people’s struggles, including resistance to patriarchy. Kim Jee Un (김지은), the association’s director and a leader of its singing group,recalled how theirfirst performance in early 2025 deeply moved their audience, ‘because when they thought of minjung-gayo, they often thought of only men singing’. The group intentionally uplifts protest music written by women about women’s struggles, since there are very few songs like this – and ‘some are written by men with sexist content’, Kim explained. Beyond expanding minjung-gayo’s role in women’s liberation, Korean activists today have also reimagined the genre’s relationship to mainstream music like K-pop to condemn political violence and attract new members to their struggle.

K-Pop for Impeachment

![]()

A mobilisation on 6 December in anticipation of Yoon Suk-Yeol’s impeachment vote the following week. Credit: International Strategy Center.

We are singing; we will get better.

We remember the days foolishly wasted away.

Still, isn’t it good?

Even through a river of tears

We are here together.

Isn’t it funny?

If we had been sitting around crying

We would have never met in this world.– ‘Isn’t That Good?’ (좋지 아니한가), 2022 cover by YUDABINBAND (YdBB).

On 3 December 2024, right-wing President Yoon Suk-Yeol declared martial law allegedly to ‘safeguard constitutional order and national stability’ against ‘anti-state elements’, including supposed pro-North Korean forces undermining the government. His declaration of martial law triggered massive protests and encampments in Seoul, despite the freezing winter nights. Within two weeks, Yoon was impeached by the National Assembly. The movement that ultimately toppled him grew from the 2016–2017 candlelight protests against Park Geun-hye, a far-right leader and the daughter of former military dictator Park Chung-hee. Both movements deployed a remarkably hybrid musical arsenal.

In addition to traditional minjung-gayo songs performed at rallies, organisers incorporated the popular genre K-pop into their mobilising strategy. For instance, K-pop songs were played during the 2016–2017 protests, interspersed between political speeches and slogans. One such song is Girls’ Generation’s ‘Into the New World’ (다시 만난 세계), its lyrics about a general sense of ‘not giving up’ reinterpreted as a vision of collective liberation from the right-wing regime.

Kim described the commotion this caused among long-time activists who complained that K-pop music and light sticks (popular accessories that fans take to K-pop concerts) were ‘ruining the tradition’. Yet she maintained that a movement is about the people: if K-pop played a role in encouraging young people to return week after week, it should have a place in the struggle.

Once Again, Forward! 또 다시 앞으로!

![]()

Members of Maru (left) and norae-pae I-eum (right). Credit: Maru and Seoul Women’s Association.

Those bitter years, those filthy, fearful days.

Again, let’s rise above them

And march to the rhythm of history.

One! Two! Three!

Forward! Once again, forward!– ‘Once Again, Forward!’ (또 다시 앞으로)

![]()

Solidarity action with Venezuela, 10 January 2026. Credit: International Strategy Center.

The same Korean movements that mobilised against Trump’s visit during APEC have now called for an International People’s Action Denouncing One Year of the Trump Regime. This declaration condemns the Trump administration’s imperialist violence across the world, from backing and funding the ongoing genocide in Palestine to the recent bombing of Caracas, Venezuela, and kidnapping of President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Deputy Cilia Flores, on 3 January 2026 (you can find a poster here, created by the International Peoples’ Assembly – one image among many to be help up at Venezuela solidarity rallies across the world). Ultimately, people’s movements from Korea to Venezuela remind us that the struggle continues, and so do its songs.

Warmly,

Tings Chak

Art Director, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

From | Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research via This RSS Feed.