By Isabella Pellerito Lucy, World BEYOND War, January 13, 2026

The first time my Girl Scout troop traveled to sell cookies, we hopped on a bus to a small military base north of Seoul—within scope of North Korea’s short-range missiles.

For our safety, we traveled in a tourist bus to mask the large group of Americans on board, checked in at the guardshack with our military IDs, disembarked, unloaded, and began our sale with a short, two-hour window to minimize risk. Soldiers swarmed our booth, eager for a taste of home and a distraction from the monotony of living and working on a bare-bones base in rural South Korea. We sold every box.

The daughter of Department of Defense educators, I was born in Germany, and grew up in South Korea and Italy. After my brothers and I were born, my mom, an Air Force veteran and former intelligence officer, transitioned into school counseling, and my dad, a historian and former contractor, became an elementary school teacher. The places I grew up in make up three of the most militarily-occupied countries in the world. As civilians living in military communities, my family had access to all the base’s amenities: education at Department of Defense Dependents Schools, youth sports through Morale, Welfare & Recreation, food at the Commissary, shopping at the Base Exchange, and more. Later on, I write about how KPOP star G-Dragon now lives where I used to catch the bus and how my middle school was demolished to create an urban park.

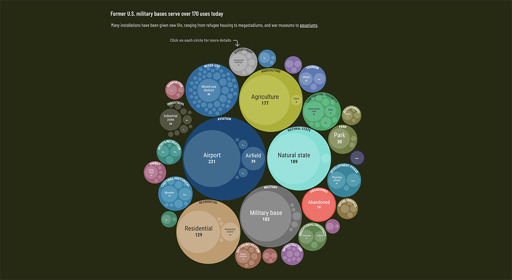

If I ask you to picture a military base, chances are a scene from a Marvel movie will pop into your head: some version of a massive, sprawling, high-tech, compound filled with soldiers in formation and American flags everywhere. Today, many military bases have that plus all the comforts of home: single-family dwellings, schools, fitness centers, shopping complexes, places of worship, movie theaters, fast food joints, and more. This is by design. In 1945, the Army permitted families to begin accompanying service members abroad, prompting an explosion of sprawling, city-like bases that exist to this day. Currently, the U.S. military has over 800 bases outside the U.S. and its territories, from single-shack sentry stations to full-fledged Little Americas, replete with Taco Bells, football fields, and massive cars. But what happens when wars end, leases expire, or local pressure brings the troops home?

Not all bases are created equal

If the last thing you may expect to see in the desert is a Cinnabon, you’re not alone.

Missions to bases in the Middle East are considered “hardship deployments.” In order to cushion tours, the military boasts amenities ranging from fast food outlets—Cinnabon, Burger King, Pizza Hut, and KFC—to indoor swimming pools, movie theaters and spas in addition to infrastructure like post offices, fitness centers, and hospitals. As a kid, I was often stupefied that we could go on base in Italy and things would look very much the same in England or Belgium—even down to the floor layouts at the Commissary.

David Vine, author of Base Nation and expert on the U.S. military presence abroad*,* groups bases into three categories. Small bases, also known as lily pads, often rely on contractors (or a handful of troops), are worth less than $10 million, are smaller than 10 acres, and may not be in constant operation. Medium bases house soldiers and have some amenities, like fitness centers, but no family members. Main operating bases, or little Americas, are worth more than $10 million, are larger than 10 acres, and usually employ 200 or more service members in addition to their families. I’ve also included the expected infrastructure and amenities based on classification.

READ THE REST HERE.

The post Post-Base Urbanism: What Happens to Former U.S. Military Bases Abroad? appeared first on World BEYOND War.

From World BEYOND War via This RSS Feed.