There are many ways in which one section of a society can dominate or oppress another. Not all of these count as forms of exploitation, at least if that word is used in anything like a Marxist way.

There can even be forms of non-exploitative economic oppression. If a group is systematically denied employment and thus lives a precarious existence on the edges of society, begging or stealing enough to stay alive, they’re certainly being economically oppressed. In fact, there’s a pretty clear sense in which they’re more economically oppressed than working-class people with secure and comfortable jobs. But, they’re not being exploited.

In his book Class Counts, the sociologist and analytical Marxist thinker Erik Olin Wright offers a complicated three-pronged definition of exploitation:

-

The “material welfare” of one group “causally depends on the

material deprivations of another.”

In other words, Group A is better off because Group B is worse off. If Group A are the beneficiaries of inherited wealth, Group B are not, and there’s simply no economic interaction between the two, this condition isn’t met. Ideals of egalitarian justice might demand redistribution from A to B, and you could stretch and say that A is better off than B because this hasn’t happened yet so in that sense they’re better off “because” B is worse off, but Wright is clearly holding out for a more robust causal connection than that.

-

This causal relation involves the exclusion of the exploited group “from access to certain productive resources.”

In the case of slaves (wholly) and serfs (partially), the exploited group are excluded from control over themselves. Modern proletarians aren’t excluded from that productive resource, but they’re excluded from control over the means of production. That’s what makes them “doubly free” in Marx’s acid formulation in Capital—free to move around and make contracts with any capitalist who will have them, but also “free” from any realistic way of supporting themselves except submitting to one capitalist or another.

-

The “causal mechanism which translates” this exclusion into the difference in welfare between the groups “involves the appropriation of the fruits of labor of the exploited by those who control the relevant productive resources.”

So, whatever the details in a particular economic system, the end result is that some of what’s produced by the exploited group ends up in the hands of the exploiters. Even if both of the first two conditions are met but this one is not, Wright argues, we’re in the realm of “nonexploitative economic oppression.” For example, if Group A conspires to deny arable land to Group B so they can hoard it all for themselves, and as a result Group B all become self-employed fishermen instead of self-employed farmers (and, in the relevant natural conditions, fishermen make a far more meagre living than farmers), A is doing better than B because B has been excluded from a productive resource, but this still isn’t exploitation.

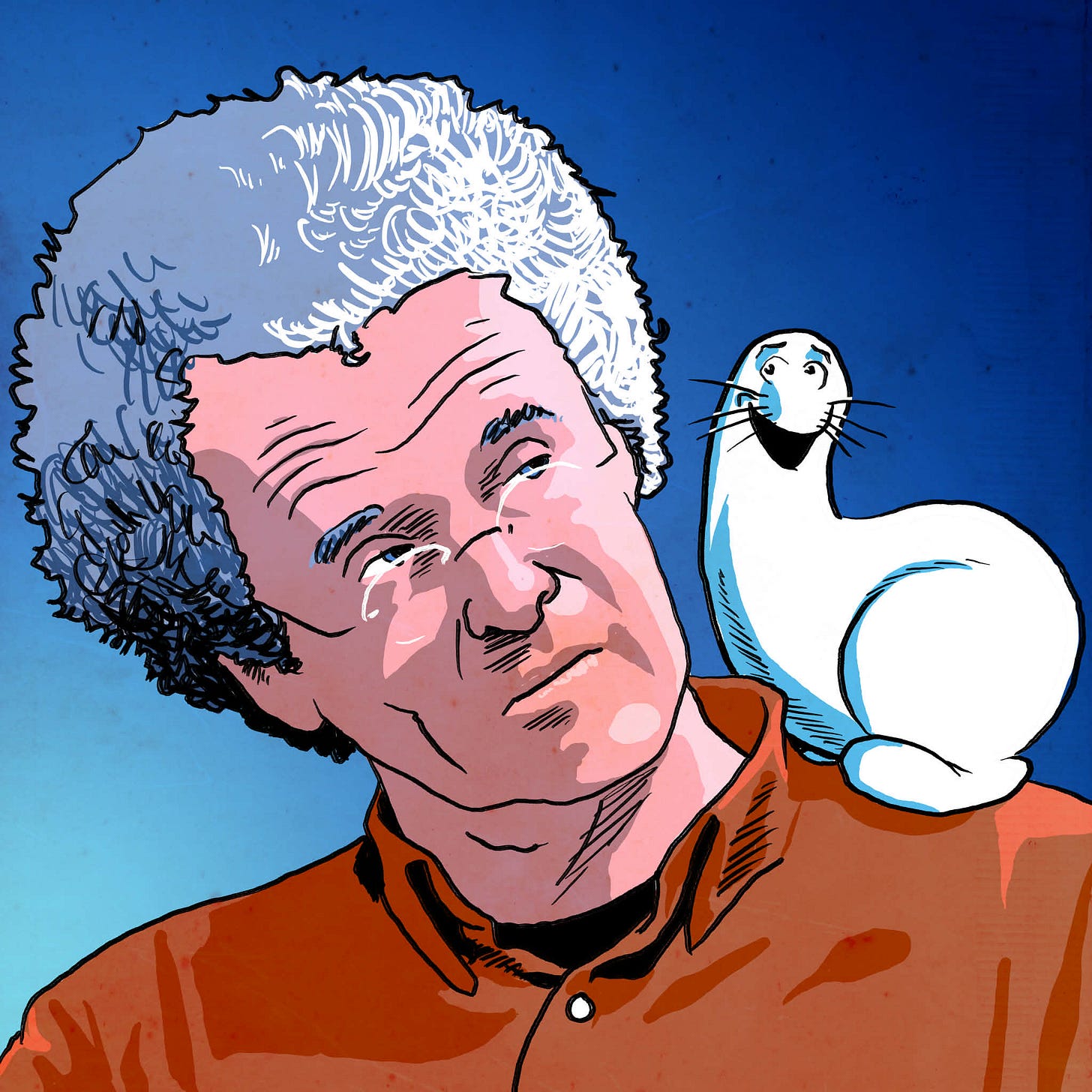

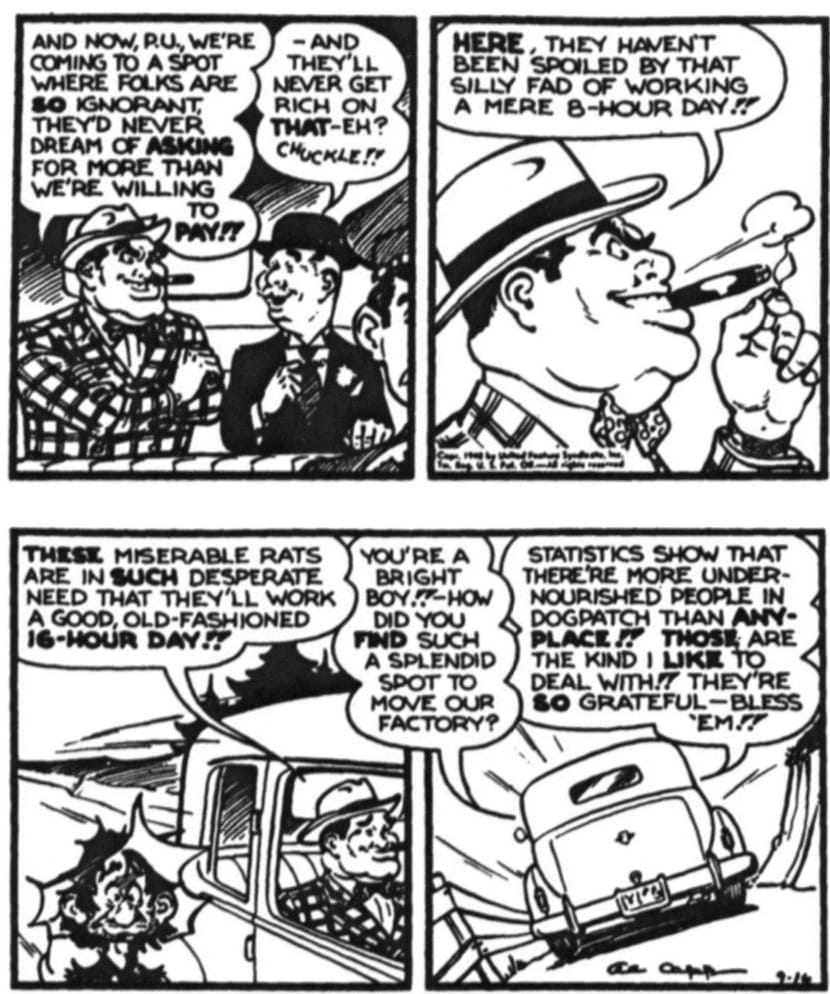

This is a general account of exploitation that can be applied to any form of class society. But Wright wasn’t an economic historian of feudalism or ancient slave societies. He was a social theorist focused on thinking about the society in which he actually lived. And in the first chapter of Class Counts, he illustrates the dynamics of exploitation under capitalism with a vivid and goofy example I love very much, drawn from a storyline from the late 1940s in the comic strip Li’l Abner.

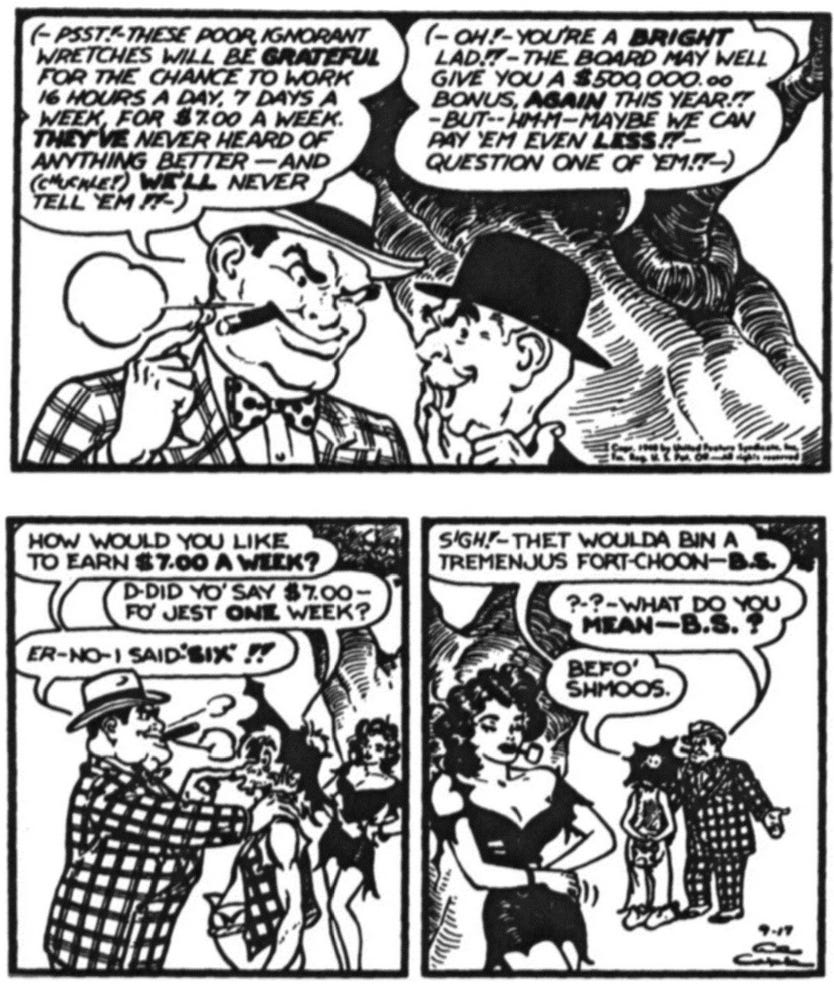

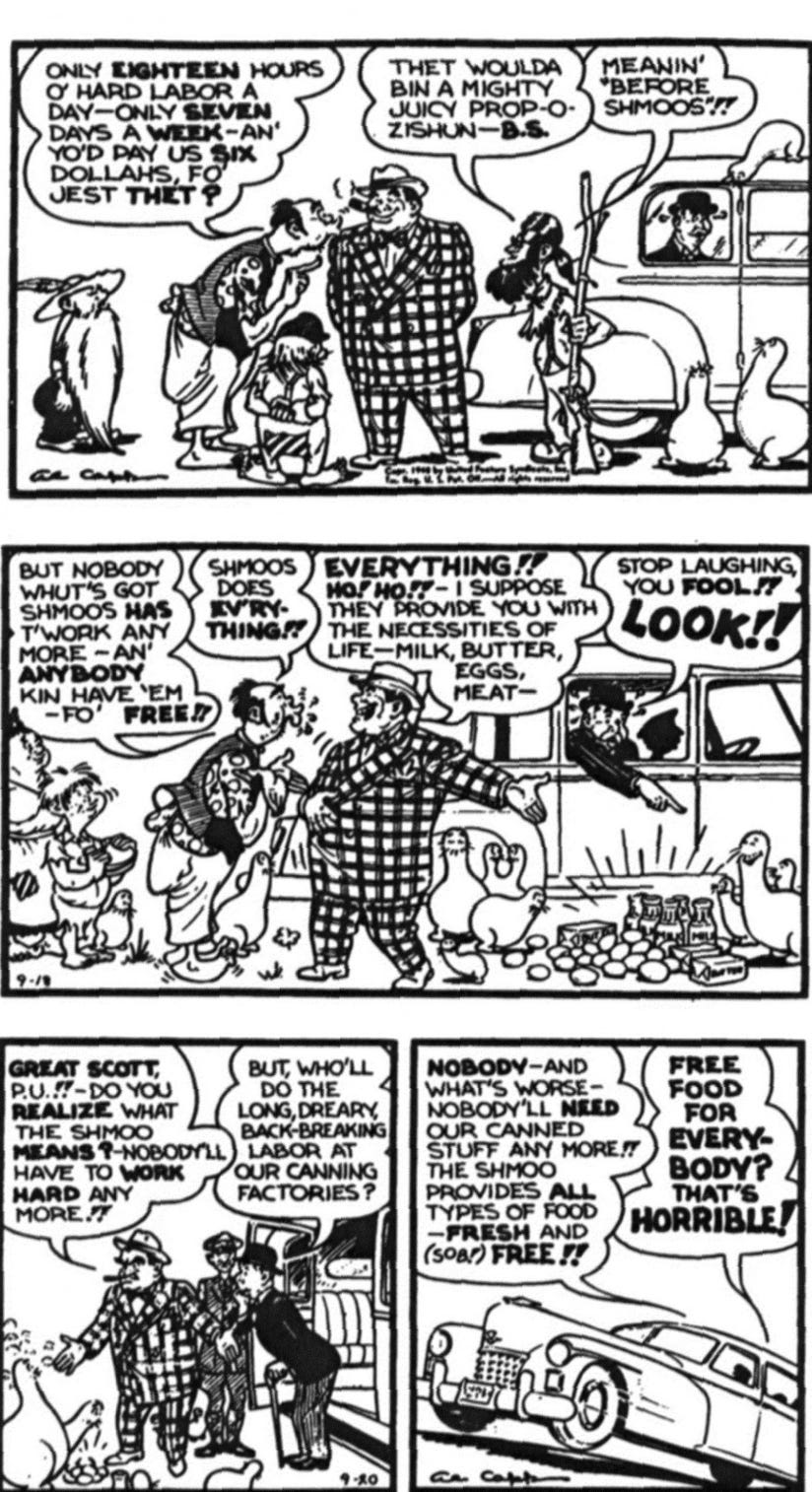

Li’l Abner, a resident of the hill-billy community of Dogpatch, discovers a strange and wonderful creature, the “shmoo,” and brings a herd of them back to Dogpatch. The shmoo’s sole desire in life is to please humans by transforming itself into the material things human beings need. They do not provide humans with luxuries, but only with the basic necessities of life. If you are hungry, they can become ham and eggs, but not caviar. What’s more, they multiply rapidly so you never run out of them. They are thus of little value to the wealthy, but of great value to the poor. In effect, the shmoo restores humanity to the Garden of Eden. When God banished Adam and Eve from Paradise for their sins, one of their harshest punishments was that from then on they and their descendants were forced to “earn their bread by the sweat of their brows.”

The shmoo relieves people of this necessity and thus taps a deep fantasy in Western culture.

The consequences of the shmoos being introduced to Dogpatch are grim from the point of view of the would-be exploiters of Dogpatchian labor:

Given that the second condition in Wright’s general account of exploitation is only met under capitalism by the exclusion of workers from the means of supporting themselves independently of capitalists, the capitalists in the comic rightly see the shmoos as an existential threat to their profits and (mostly) succeed in wiping them out.

The basic political point of all this is pretty clear even in the original comic, and the time Wright made it to Dogpatch, the shmoos and their anti-capitalist implications had already been explored in a lecture his friend G.A. Cohen gave on British television in the 1980s. But Wright managed to milk a surprising amount of further insight from the parable.

How, Wright asks, would the introduction of shmoos impact the material interests of either workers or capitalist?

That depends on the level of shmoo generosity. If the shmoo “provides less than bare physical subsistence,” it probably benefits both groups. Having some shmoos makes the workers lives slightly less hard and also enables capitalists to pay lower wages because part of the workers’ needs are met outside the market. (In phases of capitalist history where dual incomes were less standard, the domestic labor of housewives often played a somewhat shmoo-ish role for male workers.) “At the other extreme, if shmoos provide for superabundance, gratifying every material desire of humans from basic necessities to the most expensive luxuries,” this too would probably serve the interests of both groups. In between, though, the effect on the interests of capitalists and workers is sharply divergent, which Wright illustrates with this diagram:

Assuming such “modestly generous shmoos,” we can consider four possible shmoo-distributions: “everyone gets a shmoo; only capitalists get shmoos; only workers get shmoos; and the shmoos are destroyed so no one gets one.” Wright further assumes that everyone, in choosing between these options, will be motivated by nothing but rational self-interest. Obviously human beings are very often motivated by things other than rational self-interest. But this is just to say that, as valuable and illuminating as class analysis can be, it can’t explain everything.

Wright also assumes homogenous material interests within classes for the purposes of shmoo-analysis. That certainly isn’t because he of all people isn’t aware that different sections of classes (i.e. small and large capitalists, or skilled and unskilled workers) can have divergent interests on some issues, or that the economic situations of particular individuals can be complicated. In fact, one of Wright’s most important contributions to Marxist theory was his account of “contradictory class locations,” which I talked about a bit here. But his view, spelled out nicely at the beginning of his later book Classes, is that different levels of abstraction are useful for different purposes. Just as political maps that just show you borders and names of jurisdictions, topographical maps, relief maps, and so on all capture different aspects of the same reality and one might be more useful than other depending on what we’re trying to do, we might opt for either a simple two-class map of workers and capitalists or a messy and complicated map of contradictory class locations depending on our analytical purposes.

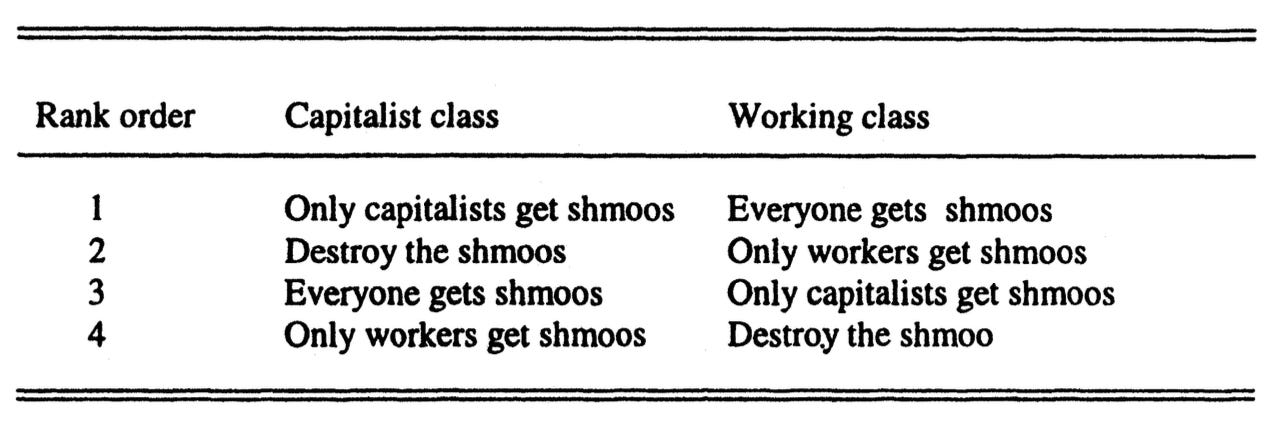

In this case, sticking with the two-class map, rational self-interest, and modestly generous shmoos, Wright gives us the starkly different “rank ordering of preferences for the fate of the shmoo by class location”:

The capitalists’ preference-ordering is pretty self-explanatory. The workers’ ordering makes sense once you realize that everyone getting shmoos is at least a little bit better for workers than no one getting shmoos, and only capitalists getting shmoos is at least a little bit better for workers than shmoo-eradication (remember, no tender altruism for either shmoos or capitalists is at play here, just material interests!) since the capitalists having to spend less on their own consumption means they have more left over to spend on hiring workers.

As Wright notes, we can see a glimmer here of what it might mean for Marxists to call workers the “universal class,” since the workers’ preference ordering “corresponds to what could be considered universal human interests.” (Fewer humans flourish as we descend each rung of that ordering!) And this is exactly the preference ordering that a rational agent would choose from behind Rawls’ veil of ignorance.

When we move from the whimsical fantasy of the shmoos to the class politics of the real world, an interesting analogy can be drawn from labor scholar Shaun Richman’s book Tell the Bosses We’re Coming. Richman tells the story of the “Treaty of Detroit” in 1950. The United Auto Workers

began the postwar period with an audacious demand: a 30 percent wage increase accompanied by no rise in the price of cars. This demand was put forth by Walter Reuther, then a vice president of the union, a few weeks after the Japanese surrender that ended the Second World War. At the time, people were understandably worried that the country would return to an economic depression once wartime spending on production was phased out. Reuther was convinced that the key to staying out of a Depression was to put more money in workers’ pockets so that their rising living standards would drive the demand for consumer goods and keep the factories humming.

This was a demand for income redistribution. It’s the demand that earned Reuther the sobriquet “the most dangerous man in Detroit.” He was so christened by George Romney (father of Mitt), who headed the auto industry association, because “no one is more skillful in bringing about the revolution without seeming to disturb the existing forms of society.” Workers who had long experienced price increases in food, shelter, and consumer goods that eroded whatever wage gains they were able to win rallied to the cause. The strike, which began on November 21, 1945, was the first time that the UAW completely shut down production at all of GM’s facilities. Workers at Ford and Chrysler stayed on the job, so that GM would lose business to its competitors and be more likely to settle what the union hoped would be a pattern for the other car companies.

This was part of a broader wave of labor unrest. That winter’s strike wave brought two million workers out on picket lines across the American economy. But the UAW’s strike at GM was an unusually long and bitter one. It was moderately successful. The auto workers got a wage increase, though GM still raised the price of cars.

For every year that followed, the UAW would single out one of the Big 3 auto companies for strike preparation and wage and benefit demands that aimed for significant, permanent improvements in workers’ standard of living. In 1949, Chrysler bore the brunt of a 104-day strike after refusing to match Ford’s fully paid pension. Out of this annual turmoil came the Treaty of Detroit. General Motors wanted five years of labor peace, and the UAW made them pay for it with pensions and health insurance.

In America in 2026, we’re so used to employer health insurance that it’s hard to put yourself in the head of a 1950 trade unionist trying to decide whether to throw in the demand. Back then, though, it was controversial.

Unions had begun to negotiate fringe benefits during the Second World War. After the War Labor Board froze wages to combat infla tion, it exempted fringe benefits from the restrictions. This “Little Steel Formula” gave unions wiggle room to make some material gains for their restive members. Many unions emerged from the war years with employer-sponsored health insurance and other benefits.

But not so much the CIO unions. Union leaders like Walter Reuther, who were more social democratic in their outlook, viewed health care and enhanced retirement benefits as the purview of the federal government. They wanted to win these things as universal rights for all Americans, as a part of a renewed New Deal.

This vision was frustrated by the Republican congressional victo ries in the 1946 midterms, but even congressional Democrats didn’t feel the same urgency of the Depression years to put money in work ers’ pockets even at the risk of incurring the wrath of the ruling class. At their 1946 convention, CIO leaders vowed not to wait “for per haps another ten years until the Social Security laws are amended adequately” and to use their collective bargaining power to address their members’ health and retirement security. The UAW believed that by forcing all the auto companies to pay for the same benefits for their employees, these benefits would be taken out of competition. Reuther’s hope was that by loading these additional payroll costs onto the auto companies’ bottom line, it would give them a financial incentive to lobby the government to assume these responsibilities.

And yet. It’s been 76 years since the Treaty of Detroit, and General Motors has yet to endorse Medicare for All. Why is that?

General motors has very little reason to care about whether Blue Cross Blue Shield can turn a profit. And while a properly class-conscious capitalist may understand that an injury to one is an injury to all, as Paul Heideman emphasizes in his new book Rogue Elephant: How the Republicans Went from the Party of Business to the Party of Chaos, the incentives for capitalists to band together in class-conscious pursuit of their collective interests have actually been fairly weak in the United States compared to many other countries around the world. That sounds counterintuitive, given that capitalist interests are so well catered-to here, but the general pattern is that militant employers’ associations and such generally arise in reaction to class formation on the proletarian side of the struggle, for the simple reason that capitalists don’t need to band together in solidarity with each other when the exploitation machine is humming along without interference.

If it’s implausible that capitalists outside the health insurance industry are moved by tender concern for their brother-capitalists, it could be that they’re moved by at least a dim awareness that it might not be the best idea to let their workers have health-care shmoos.

Thanks for reading Philosophy for the People w/Ben Burgis! This post is public so feel free to share it.

From Philosophy for the People w/Ben Burgis via This RSS Feed.