This is part three of our analysis of Noam Chomsky. In**part one**, we analyzed his linguistics; in part two, we examined his relationship with power.

He began his political writing through activism against the Vietnam War, and his first book-length publication, American Power and the New Mandarins, is a 400-plus-page monograph that incorporates his early political essays, including “The Responsibility of Intellectuals” and “On Resistance.” In this work, Chomsky argues that American power is no longer exercised primarily by the older class of robber barons and industrial capitalists, but increasingly by a technocratic stratum embedded in institutions of expertise. Power, he suggests, resides in “the research corporation, the industrial laboratories, the experimental stations, and the universities…the scientists, the mathematicians, the economists, and the engineers of the new computer technology”—a group he refers to as the “new Mandarins.”1

Chomsky largely launders this claim through quotation and attribution, rarely stating the thesis in his own declarative voice. Nevertheless, the position is unmistakably his. Later in the same discussion he poses the explicitly normative question: “Quite generally, what grounds are there for supposing that those whose claim to power is based on knowledge and technique will be more benign in their exercise of power than those whose claim is based on wealth or aristocratic origin?”2 The question only makes sense if Chomsky accepts the premise he dances around instead of stating directly —that technocratic expertise has become a central basis of political power in the United States. This shift, however, represents not a displacement of capitalist power, but a reorganization of its managerial apparatus.

Historic.ly is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The rest of the book is filled with hand-wringing and finger-waving about how American schools and universities are not independent centers of free inquiry, but function instead as the long arm of the state. Their primary role, in Chomsky’s account, is to train the technocratic elite—the experts and intellectuals who supply the ideological cover for American imperialism abroad and domestic repression at home.

He concludes the analysis of intellectuals with his signature essay, “The Responsibility of Intellectuals,” where he finally states the moral core of his argument without laundering it through quotation. Intellectuals, Chomsky argues, constitute a privileged minority uniquely positioned to uncover truth precisely because of their structural advantages. As he writes, “Intellectuals are in a position to expose the lies of governments, to analyze actions according to their causes and motives and often hidden intentions”3 and these intellectuals possess “the leisure, the facilities, and the training to seek the truth lying hidden behind the veil of distortion and misrepresentation, ideology, and class interest through which the events of current history are presented” and it is their responsibility to “speak the truth and expose the lies.4”

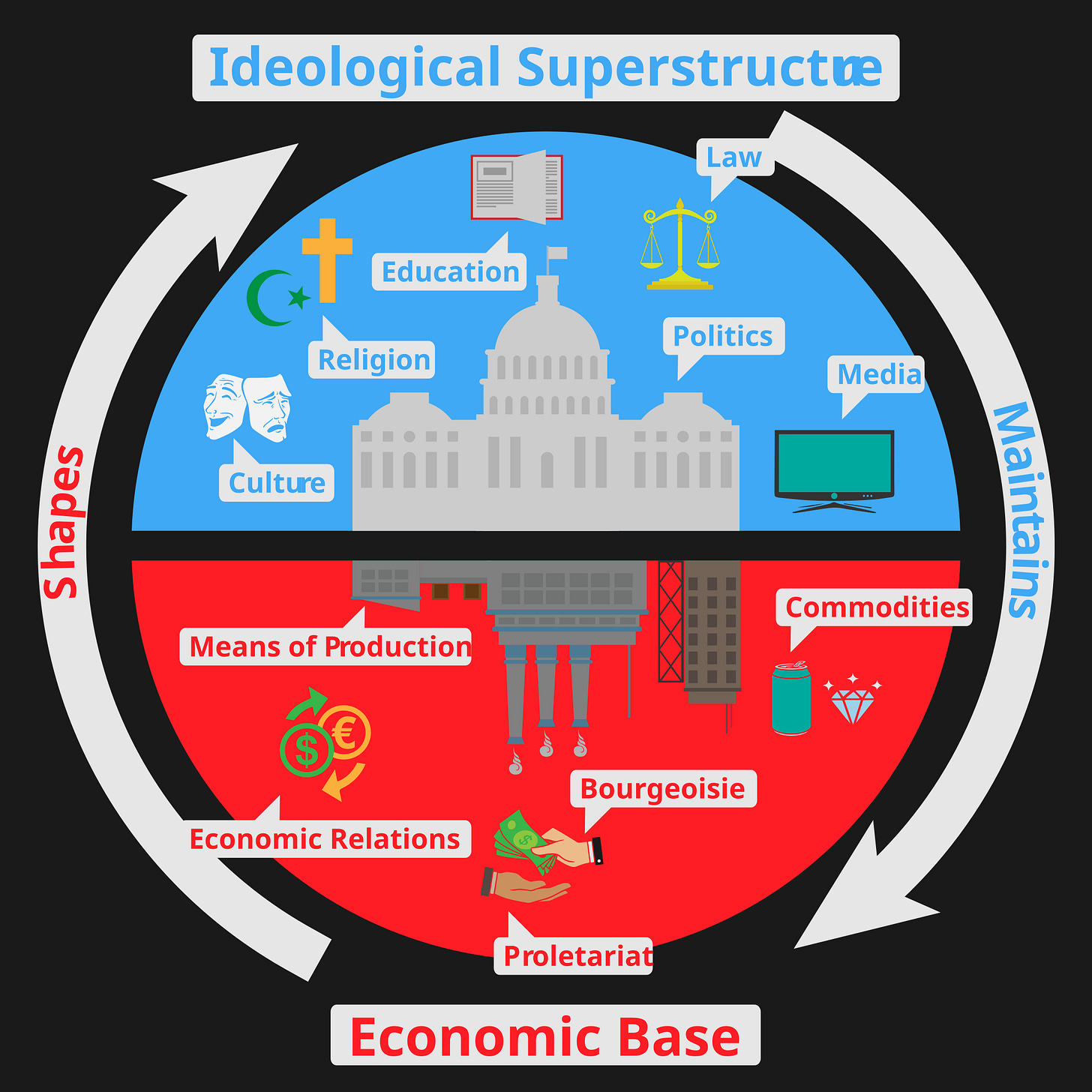

The framework Chomsky advances as the “responsibility of intellectuals” rests on a configuration of assumptions about intellectual agency in a capitalist, bourgeois-led society. The very privileges that grant intellectuals leisure, institutional access, and training also align their class interests with capitalist hegemony, rendering them among the least likely actors to challenge its foundational premises. Ironically, Chomsky spent nearly 300 pages detailing how intellectuals repeat the government line, accept without question the legitimacy of imperial state interests, and rationalize violence within the language of expertise. If it were simply a moral failure, then one can shame these intellectuals to “tell the truth” through polemical exposition. But the consistency with which they reproduce elite premises—documented throughout Chomsky’s own account—indicates that this behavior is not aberrational, but constitutive of their institutional role within an imperial system.

While Chomsky meticulously maps the mechanism of deceit employed by the New Mandarins, he stops short of analyzing the structural necessity of that deceit. He treats the betrayal of the intellectuals as a moral failure of the ‘priesthood,’ believing that exposing their hypocrisy will shatter their power.

However, a materialist analysis reveals that these intellectuals are not merely failing their moral duties; they are successfully fulfilling their institutional functions. By focusing on the lies of the experts rather than the class interests that demand those lies, Chomsky preserves a liberal faith in the power of truth to constrain empire—ignoring that the empire is sustained not by the credibility of its Mandarins, but by the material force of its economic base.

What American Power and the New Mandarins ultimately reveals is not the failure of intellectuals to live up to their moral responsibilities, but the limits of moral critique itself when detached from class analysis. Chomsky meticulously documents how intellectuals rationalize imperial violence and translate domination into the neutral language of expertise. Yet, by framing this as a problem of vigilance and courage, he preserves the liberal hope that truth-telling by privileged actors can constrain power.

The evidence he assembles points to a different conclusion: intellectuals do not merely fail to oppose imperial power—they are selected, trained, and positioned to reproduce it. Exposure, under these conditions, does not threaten domination; it stabilizes it. The problem is not that intellectuals have failed to tell the truth, but that the social role of the intellectual is inseparable from the reproduction of the system that defines which truths matter in the first place.

These theoretical contradictions manifest concretely in Chomsky’s Vietnam analysis. When engaging with the text, Chomsky’s disciplinary respectability politics produces dense prose that obscures his analysis.

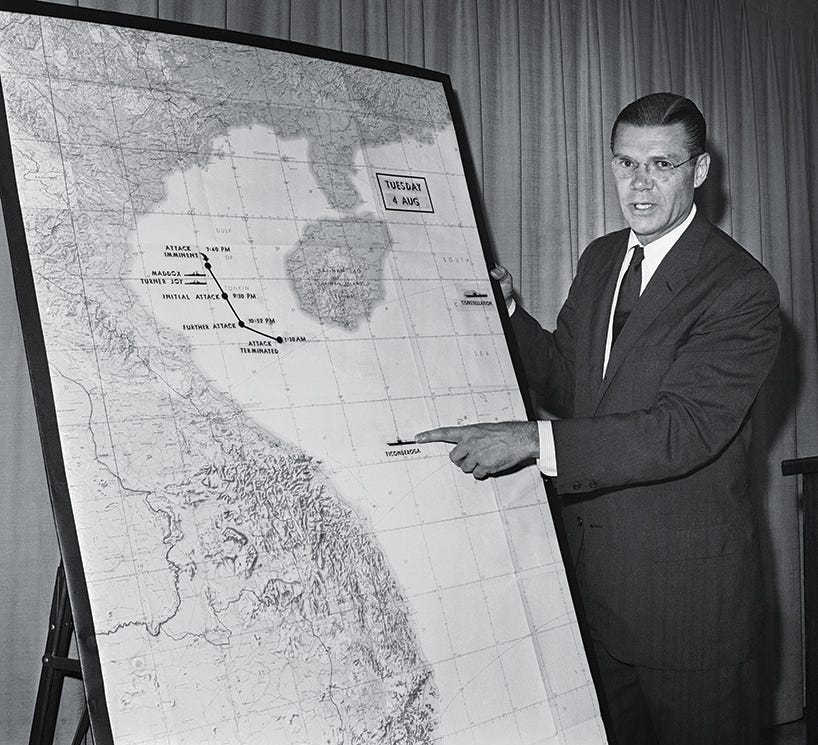

One stark example appears in the chapter “The Logic of Withdrawal,” where Noam Chomsky introduces the term pacification in the context of the U.S. military’s assumption of that role. He notes that Senator Young reacts to reports that South Vietnamese forces are unwilling to perform what amounts to police work, requiring so-called “pacification” to be taken over by the American army. Chomsky then quotes the senator at length: “If the South Vietnamese forces of Prime Minister Ky are so inadequate in numbers, intelligence, and training that they cannot handle entirely the pacification program in the villages … then instead of Americans trying to train, indoctrinate, and pacify an alien people, the time is long past due for us to withdraw to our coastal bases and eventually from Vietnam.”5

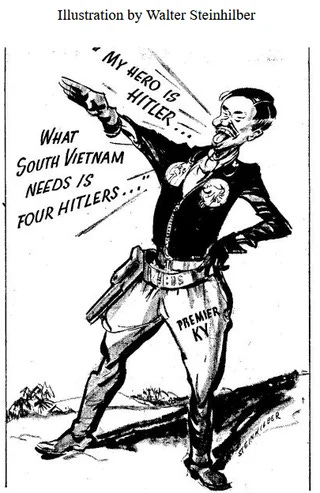

While Chomsky does document the devastation of rural villages resulting from American policy, he never clearly conveys to the reader what pacification actually meant in practice. The term functions as a military euphemism that sanitizes the scale and character of the violence involved. Had he instead juxtaposed this language with Nguyễn Cao Kỳ’s own words—who stated in a 1965 interview that “the situation here [Vietnam] is so desperate now that one man would not be enough. We need four or five Hitlers in Vietnam”—the meaning of U.S. policy would have been unmistakable. Under this framing, pacification is revealed not as stabilization or policing, but as the application of overwhelming, systematic violence against a civilian population.

Premiere Ky said Vietnam needed Four or Five Hitlers

In other words, by pacification, the United States was providing the role of the “four or five Hitlers.” It was unleashing genocidal violence against rural populations—destroying villages, killing civilians, and breaking the material basis of life itself. If the South Vietnamese regime could not survive without this level of violence against its own population, that fact alone exposes pacification not as policing or stabilization, but as mass destruction used to sustain an otherwise untenable political order.

While Chomsky accurately describes why the United States continues to support the South Vietnamese government—“Nor is it obscure why the American government continues to use its military force to impose on the people of Vietnam the regime of the most corrupt, most reactionary elements in Vietnamese society. There is simply no one else who will do its bidding”—he then imputes an inaccurate picture of Vietnamese society by claiming that this regime must resist “the overwhelming popular sentiment for peace and, no doubt, neutralism”6

This characterization reflects categories that resonate within American liberal discourse, but it does not accurately describe the political reality of South Vietnam. Among an overwhelmingly peasant population—especially in the Mekong Delta—peace without liberation was understood as surrender, and neutrality as the preservation of an intolerable social order. The mass demand was not for peace or non-alignment, but for a revolutionary government capable of delivering land, material survival, and national independence, even at the cost of prolonged and intensified war.

By translating a revolutionary demands of “liberation and redistribution” to “peace and neutrality” into liberal categories acceptable to American discourse, Chomsky obscures the central contradiction: pacification was not an effort to manage dissent or restore order, but the organized application of massive violence required to impose a landlord state on a population seeking revolutionary transformation.

This distortion is underscored on the very next page, where Chomsky quotes a Vietnamese doctor stating:

The Americans have demolished everything. All that we have built since 1954 is in ruins: hospitals, schools, factories, new dwellings. We have nothing more to lose, except for independence and liberty. But to safeguard these, believe me, we are ready to endure anything.

This testimony directly undermines the claim that the dominant popular sentiment was peace or neutralism; it expresses a willingness to endure unlimited suffering in pursuit of liberation.

Chomsky’s own anti-communist impulse prevents him from foregrounding this contradiction. To accept that the Vietnamese population was fighting with extraordinary determination to impose a Marxist-Leninist political order would require conceding that Marxism-Leninism functioned, in this context, as a genuinely liberatory framework capable of delivering concrete material benefits to the population—an implication Chomsky has consistently resisted throughout his work.

Another familiar pattern that Chomsky repeats many times in US policy analysis is the reliance on legalese or condemning the US for violations of international law. He says, “The disregard for law and treaty was illustrated strikingly by our behavior with respect to the Geneva agreements of 1954.7” But, by his own admission, US never signed the Geneva accord, therefore, they cannot be bound by a law or treaty they never signed. If he wanted to show blatant violations of international law, there were much more striking examples, such as the strategic Hamlet program reported in 1962, where entire villages were forcibly relocated into these strategic hamlets, that the New York Time sanitized as “ The greatest advance in the hamlets has been psychological, he said, for the erection of barbed wire and bamboo fences has given a sense of unity and identity” instead of “imprisoning the people.8”

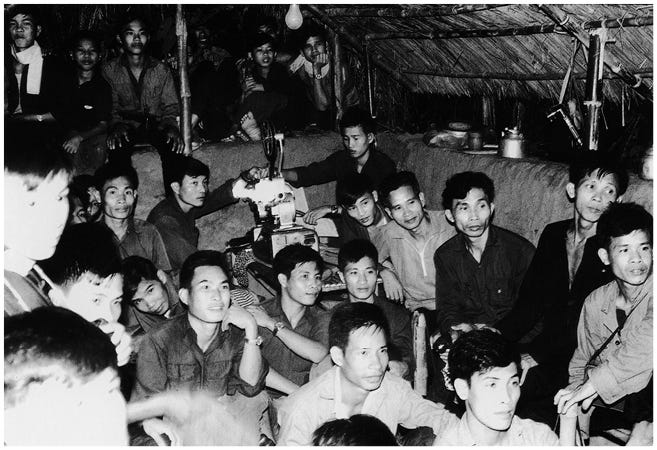

Vietnamese civilian in the Mekong Delta region, photographed during the early U.S. war in Vietnam. New York Times, December 15, 1962

By July 1967, any subscriber to The New Yorker (arguably the most “respectable” magazine in America) could read Jonathan Schell’s detailed account of how the US military was erasing the distinction between civilian and combatant. Chomsky didn’t need secret cables; he just needed to read the issue of The New Yorker that was likely sitting on every coffee table in the MIT faculty lounge. But instead, he contorts himself before coming to the conclusion, “Thus our aim was to violate our commitment at Geneva. This aim was part of our general program of “trying to safeguard South Vietnam as part of the ‘retainment’ of all or most of non-communist Asia.9”

While the conclusion is true, it misses the heart of the problem. South Vietnam was a colonial entity imposed by the US to prevent the exercise of Vietnamese Democracy. By retreating into “twisted legalese” about a treaty the US never signed, Chomsky inadvertently accepted the US framing of the conflict—that it was a diplomatic dispute gone wrong, rather than a colonial extermination campaign.

This legal framing error does not remain confined to questions of treaties or formal obligations. It directly shapes how Chomsky treats the question of Vietnamese resistance itself. He accepts the American framing, and then continues to argue about how the North Vietnamese did not commit aggression. By arguing that the North Vietnamese did not commit aggression, Chomsky falls into the trap of implying that if they had, the US response would have been justified. By even justifying the US reasoning, Chomsky doesn’t beat the war mongers in their own game, instead, he allows their reasoning to be smuggled into the minds of the reader. The stronger anti-imperial position would be: regardless of who attacked first, the Vietnamese have every right to expel a colonizing force and its collaborationist government.

But the most outrageous, is the falsehood that Chomsky promotes, where he claims, “It is curious, incidentally, that today only the United States and the “Communists” insist that South Vietnam is a separate and independent entity10” which is entirely false. Since the NLF’s Party Program calls the South Vietnamese government, “is a camouflaged colonial regime dominated by the Yankees, and the South Vietnamese government is a servile government, implementing faithfully all the policies of the American imperialism.”11

Even in his attempt to defend the People’s Liberation army, he uses the constitution of the Saigon regime,

The Saigon authorities maintain, in article 1 of the new constitution, that “Vietnam [not SouthVietnam] is a territorially indivisible, unified, and independent republic,” of which they claim to be the rulers ; article 107 of the constitution specifies that article 1 cannot be amended.

Legislative assembly of the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam), modeled on Western parliamentary forms and sustained by U.S. power.

By using their constitution, Chomsky validates their existence as a government with laws worth taking seriously. Finally, even in his defense of Ho Chi Minh, he uses criminalizing language of “aggression” (or invading a foreign country) or Insurrection (also a crime). Instead of the more accurate conclusion, Ho Chi Minh’s government was a legitimate government who was expelling a foreign invader. The legalistic defense accepts the premise that the puppet regime has a right to exist and be subverted.

What unites these analytical failures—the euphemism of “pacification,” the mistranslation of revolutionary demands as “peace and neutralism,” the legalistic contortions over unsigned treaties—is a more fundamental evasion: Throughout American Power and the New Mandarins, while Chomsky documents US atrocities and colonial war, he never acknowledges the Vietnamese People’s Liberation Army and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam as the legitimate government of Vietnam.

Village-level governance in National Liberation Front–controlled areas: peasants administering local affairs within the spaces of everyday life.

This is not a minor omission. It is the core contradiction that undermines his entire analysis.

Chomsky can document that the South Vietnamese regime is “the most corrupt, most reactionary elements in Vietnamese society” sustained only by US military force. He can show that the overwhelming majority supports the NLF. He can quote Vietnamese people declaring their willingness to “endure anything” for independence and liberty. He can expose “pacification” as mass violence against civilians.

Yet even while proving all this, he still frames the conflict through imperial categories: “South Vietnam” exists as a legitimate entity, the NLF and DRV coordination is suspect and requires apologetic defense, Ho Chi Minh sending troops south would be “aggression” rather than a government acting within its own territory. He uses the Saigon regime’s constitution as if it were a meaningful legal document rather than puppet theater.

Imperial authority did not emerge from Vietnamese society; it was imposed externally through administration, planning, and forc

He can document that the US is waging colonial war against the Vietnamese people, but he cannot state that the Vietnamese communist forces fighting that war represent the legitimate government of a unified Vietnam.

This explains every other evasion in the text. Why translate “liberation and land redistribution” into “peace and neutralism”? Because acknowledging revolutionary demands would mean accepting that the communists offered something the US puppet could never provide. Why retreat into legal technicalities about Geneva? Because stating clearly that Vietnam was one country under foreign occupation would expose “South Vietnam” as the fiction it was. Why apologize that the NLF doesn’t “really” coordinate with Hanoi? Because Vietnamese unity against imperialism undermines the premise that there are “two Vietnams.”

The Vietnamese understood what Chomsky’s framework obscures: they were not insurgents or rebels fighting against legitimate authority. They were the legitimate government and the people it represented, expelling foreign occupiers and their collaborationist puppets. The NLF and DRV were not “coordinating aggression” across an invented border—they were one nation fighting a unified liberation war. The demand was not for “peace” or “neutrality” but for what any sovereign people have the right to demand: control of their land, their resources, their political destiny.

Chomsky can expose US lies and document atrocities, but he cannot make the simple statement that follows logically from his own evidence: The Democratic Republic of Vietnam, led by Ho Chi Minh, was the legitimate government of Vietnam. The National Liberation Front represented the will of the South Vietnamese people. The Saigon regime was a US-imposed puppet with no legitimate authority. The Vietnamese communists had every right to expel the foreign invaders by any means necessary.

This is not radical rhetoric—it is the straightforward conclusion from the facts Chomsky himself presents. His refusal to state it clearly reveals the fundamental limitation of his anti-imperialism: he can oppose imperial violence but cannot affirm the legitimacy of those fighting against it. He can document colonial war but not name the colonized as the rightful victors. He can expose the puppet but not crown the revolution.

Finally, after the exposition of all the atrocities in Vietnam, Chomsky’s only prescription in his essay “On Resistance” is peaceful draft resistance, which as the critic William X explains, “only volunteers people for prison”. Ironically, the biggest contradiction in his prescription is that he states, “The argument that resistance to the war should remain strictly nonviolent seems to me overwhelming. As a tactic, violence is absurd. No one can compete with the government in this arena” when he literally demonstrated in the past 373 pages that the Vietnamese peasants were successfully doing just that.

Vietnamese youth militia member guarding a captured U.S. soldier during the Vietnam War.

The contradiction reveals everything: he can analyze revolutionary victory when it’s safely in the past, but he cannot affirm it as legitimate. He can document peasant resistance, but not acknowledge it as the exercise of rightful authority by a government defending its people against foreign invasion.

Without this clarity, anti-imperialism becomes a performance of moral anguish rather than solidarity with liberation. Readers can feel outraged about hypocrisy, appreciate sophisticated legal arguments, admire resistance from a safe distance—all while the basic question of who has the right to rule Vietnam remains obscured in euphemism and evasion.

The Vietnamese won not by exposing American hypocrisy or arguing about international law, but by organizing as the legitimate representatives of their people and fighting until the invaders left. They did not need Chomsky to validate their government’s legitimacy—they established it through revolutionary transformation of material conditions, mass popular support, and successful military resistance.

What Chomsky’s Vietnam writing ultimately reveals is that you cannot build effective anti-imperialism while accepting imperial categories about legitimacy, sovereignty, and rightful authority. You cannot oppose colonial war while treating the colonizer’s puppet as a government worth taking seriously. You cannot document popular support for revolutionaries while framing them as insurgents rather than the legitimate expression of popular will.

The tragedy is that this evasion is not unique to Vietnam. As we will see in examining Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya, Chomsky’s pattern of accepting imperial enemy construction while opposing imperial methods persists and degrades—becoming less rigorous, more accepting of propaganda, until the author of Manufacturing Consent falls victim to the very consent he claimed to expose.

Noam Chomsky, American Power and the New Mandarins (New York: Pantheon Books, 1969), 24

Ibid, 27

Ibid, 324

Ibid.

Ibid, 223

Ibid, 230

Ibid, 241

Binder, David. “U.S. Program Reported to Halt Red Advance in Vietnam in ‘62.” New York Times, December 15, 1962.

Chomsky, American Power and the New Mandarins, 242.

Ibid, 243

National Liberation Front of South Viet-Nam, “Program of the National Liberation Front of South Viet-Nam,” Digital History

From Historic.ly via This RSS Feed.