Thanks to all our readers for a great year. A quick note before the story: Ryan Grim was on Tim Dillon’s final show of 2025, discussing all our Epstein revelations. You can watch that here. And if you haven’t made your end-of-year tax-deductible gifts yet, you can support our journalism here:

Undated photo of Netanyahu and Barak in front of an Iron Dome battery, taken from Barak’s private emails.

On December 17, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced a $35 billion deal to sell natural gas to Egypt in what officials describe as the largest energy export agreement in Israel’s history. The natural gas will be produced from Leviathan, a massive field west of Haifa. “On this day,” Netanyahu wrote in a statement that day, the third day of Hanukkah, “we’ve brought another jug of oil to the nation of Israel. But this time, the flame will burn not just for eight days, but for decades to come.”

The gas export permit for Egypt came after months of delays and behind-the-scenes disputes between Tel Aviv, Cairo, and Washington. The decision is expected to reinforce the Camp David peace framework between Egypt and Israel—an arrangement strained by the Gaza genocide—while cementing Israel’s emergence as a major natural gas supplier in the eastern Mediterranean and beyond.

The deal has been more than a decade in the making—and one unlikely individual played a small, but essential role in laying its groundwork: Jeffrey Epstein. Former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak consulted extensively with Epstein on financial deals around Leviathan for years, as Barak searched for international backers for Leviathan’s development.

Epstein’s role in Israel’s gas politics contradicts the image, advanced in a recent New York Times profile, of Epstein as a confidence man who was viewed with skepticism by financial and political elites. In fact, Epstein advised financial giant JPMorgan Chase Bank on several global energy and logistics deals after the 2008 financial crisis: unsealed documents from a recent U.S. Virgin Islands’ lawsuit show Epstein engaged with British MP Peter Mandelson regarding the acquisition of natural gas assets from the Royal Bank of Scotland in 2010, and he arranged a 2011 meeting between JPMorgan executive Jes Staley and Karim Wade, son of then-president of Senegal Abdoulaye Wade, to discuss a large crude oil trade. (Later, Epstein tried to help with developing Senegal’s offshore gas as well.)

Hacked emails from Barak’s inbox reveal that Epstein shared a critical interest with JPMorgan executives in the early 2010s: development of Israel’s offshore gas fields. Private emails from Barak’s Gmail account show that the former Israeli prime minister was courting foreign investors for the Leviathan gas field, while Epstein provided close guidance behind the scenes. The documents were posted by Distributed Denial of Secrets, a non-profit whistleblower and file-sharing website. Drop Site is partnering with Jmail to make the DDOS emails available to the public.

During that period, the development of Israel’s natural gas resources was transforming into an urgent political priority. In February 2011, the same week Egypt’s President Hosni Mubarak fell from power, the region was gripped by supply shocks from attacks on the Arab Gas Pipeline by militants in Sinai. The Leviathan field, discovered in December 2010, was estimated to hold roughly half a trillion cubic meters of recoverable reserves, enough to supply the energy demands of Israel and its neighbors for decades, and transform the energy politics of the Eastern Mediterranean.

At this pivotal moment in the early months of Leviathan’s history, Epstein also helped secure a meeting between Netanyahu and senior JPMorgan leadership, a meeting which was referenced in documents from the U.S. Virgin Islands lawsuit and previously reported by the Daily Beast.

The reason for the meeting, and the nature of Epstein’s involvement, was not disclosed in the court documents, which are heavily redacted. But, whether by chance or by design, Netanyahu agreed to the meeting on March 23, 2011—the same day the Knesset Finance Committee voted on a major tax increase on natural gas exports, a key hurdle to beginning commercial development of Leviathan.

Israel’s offshore gas ambitions did not progress smoothly. By 2014, amid a brutal war in Gaza, Israeli energy tycoon Yitzhak Tshuva was facing an antitrust case against his company, Delek Group, which owned the Leviathan field together with Texas-based Noble Energy (since acquired by Chevron). Epstein coached Barak on credibly presenting himself as an expert on energy, as Barak searched for friendly partners in Europe, Russia, and the U.S. to help Tshuva’s group become compliant with Israel’s anti-monopoly law and push the Leviathan project forward.

Netanyahu ultimately forced a compromise, allowing the Delek–Noble consortium to control Leviathan, the large field for foreign exports, while selling off its stake in Tamar, a smaller field for domestic supply.

As the new gas framework was being finalized, Netanyahu’s son, Yair, was captured on tape at a Tel Aviv strip club in late 2015, drunkenly confessing that it was a corrupt bargain. In the recording, Yair told Nir Maimon, son of gas magnate Koby Maimon, who became the controlling interest in Tamar, “My dad made an awesome deal for your dad, bro. He fought, fought in the Knesset for this.” He pressed Maimon to give him some cash to pay a stripper, “Bro, my dad now arranged a $20 billion show for you and you can’t spot me [400 shekels]?”

Although Epstein stopped banking with JPMorgan in 2013, additional leaked emails from Epstein’s Yahoo account suggest elite business leaders in the United Arab Emirates continued to view Epstein as having high-level ties to the bank for years afterward. During a 2015 conference in Kazakhstan, Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem, head of Dubai Ports World, was angling for a meeting with Israeli economist Jacob Frenkel, then-chairman of JPMorgan’s international business, who had also been involved in planning the 2011 Netanyahu meeting.

After the antitrust dispute was finally resolved in 2016, JPMorgan financed a multi-billion-dollar plan to develop Leviathan. JPMorgan declined to comment for this story. This report on Epstein’s background in the Leviathan saga is part of an ongoing series investigating his connections to the intelligence communities in both Israel and the U.S.

Support Drop Site’s Reporting on Epstein

“Surprisee Suprise”

After Jeffrey Epstein was arrested for the second time on sex trafficking charges in the summer of 2019, JPMorgan initiated an internal probe, “Project Jeep,” to investigate its risk exposure from Epstein’s criminal activities. The project produced a 22-page summary of the bank’s communications with Epstein, including a bulleted list of excerpts from emails between Epstein and Jes Staley, former head of JPMorgan’s investment bank, dating back to 2008. Staley met Epstein in the mid-1990s, at the offices of The Limited, when Epstein was working as chief financial adviser to fashion mogul Leslie Wexner.

When the New York Times Magazine reported that Staley credited Epstein for setting up the meeting with Netanyahu in 2011, the bank’s spokesman told the paper that JPMorgan “neither needed nor sought Epstein’s help for meetings with any government leaders.” The bank’s statement appears to contradict its own analysis in “Project Jeep,” which includes several examples of Epstein introducing senior bank leadership to government leaders in the UK, Africa, and the Persian Gulf. Epstein “appear[ed] to maintain relationships with a number of senior business executives and senior government officials globally,” JPMorgan’s attorneys wrote.

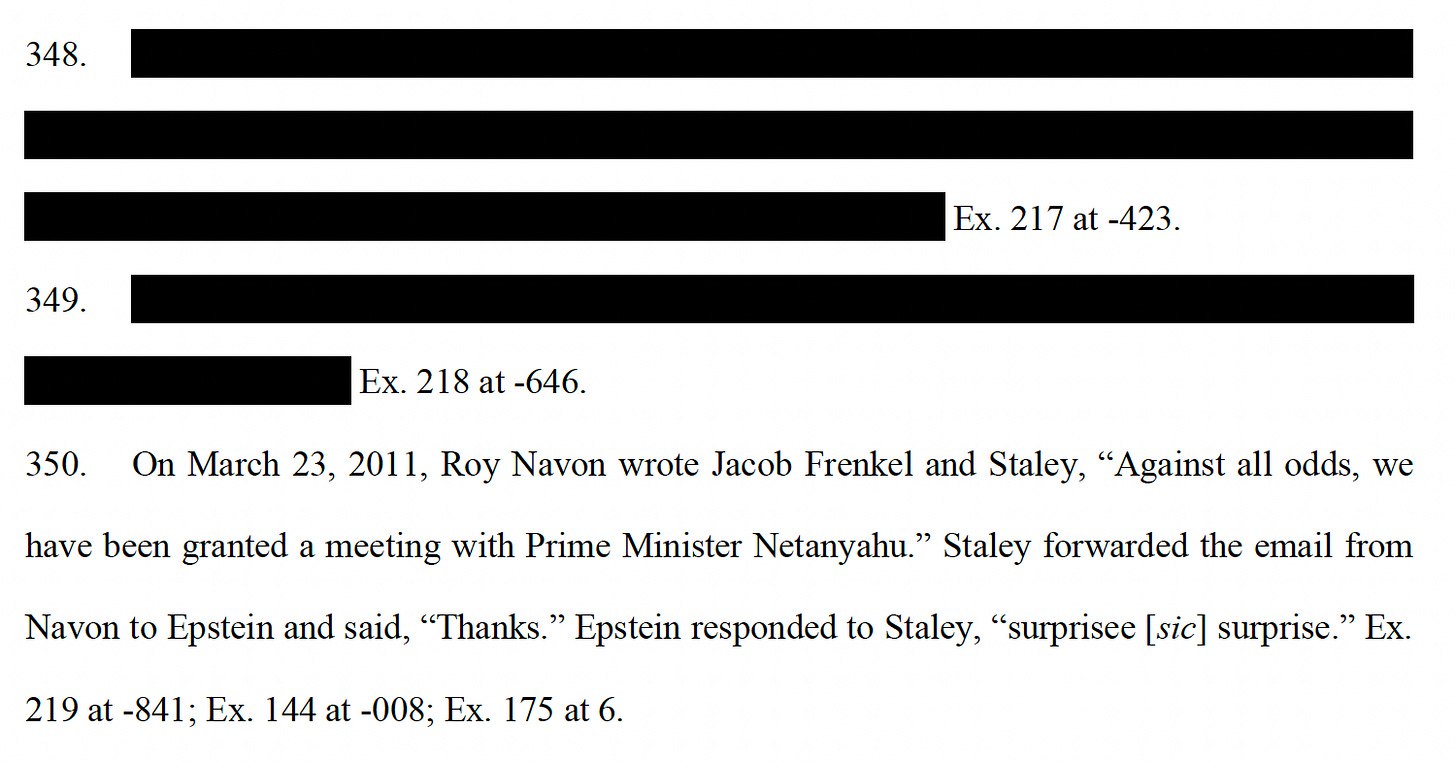

On March 23, 2011, Roy Navon (head of JPMorgan’s Israel office) sent an email to Staley and Jacob Frenkel, writing, “Against all odds, we have been granted a meeting with Prime Minister Netanyahu.” Staley forwarded the email to Epstein with a note: “Thanks.” Epstein replied: “surprisee suprise.”

Redacted excerpt from U.S. Virgin Islands v. JPMorgan Chase, August 15, 2023.

Staley received confirmation of the Netanyahu meeting on the same day as a key vote being held in the Knesset Finance Committee on the “Sheshinski” bill—named for an advisory committee headed by an esteemed Israeli economist—that would increase the Israeli government’s tax on offshore oil and gas profits.

Netanyahu framed the gas tax as an effort to balance the needs of Israeli citizens, who were facing rising energy costs, with the demands of the field’s investors, who were threatening to pull the plug on the project. At the eleventh hour, lawmakers were attempting to add language restricting the government’s ability to raise taxes again in the future—but the objection was dropped after the Finance Minister promised Netanyahu would commit to “tax stability” at the next cabinet meeting.

Major international banks were already positioning around the Leviathan project: Barclays and HSBC—two of JPMorgan’s rivals—were the exclusive financial advisers for the Leviathan investors’ smaller field, Tamar, and had loaned nearly $400 million the previous year.

At around the same time Staley received Navon’s email confirming a meeting with Netanyahu, the minutes for the marathon Sheshinski session show lawmakers were debating whether “financing expenses” would be recognized in calculating the new levy—a decision that would have direct implications for how investors and lenders modeled cash flows from the Leviathan project.

Epstein’s emails with Jes Staley, March 23, 2011.

After the successful Sheshinski vote, Netanyahu phoned Finance Committee chair MK Moshe Gafni to congratulate him, calling the law “among the most important for Israel’s economy.” One week later, on March 30, the Sheshinski law was passed, lifting the state’s take on natural gas profits to more than 50 percent.

“Really a Lucky Guy”

Leviathan sits on one of today’s central geopolitical fault lines: Europe’s dependence on Russian gas. Israeli gas could diversify Europe’s supplies by bringing new, non-Russian gas into European markets. Russia’s state-backed energy group, Gazprom, made a bid for ownership in Leviathan in 2012, but it was rebuffed by the field’s American owners from Noble Energy. Nevertheless, in February 2013, Delek and Noble’s smaller gas field, Tamar, arranged an exclusive deal with Gazprom to offtake Israeli liquefied natural gas and market it in Asia — a deal some participants hoped to parlay into a future role in Leviathan as well.

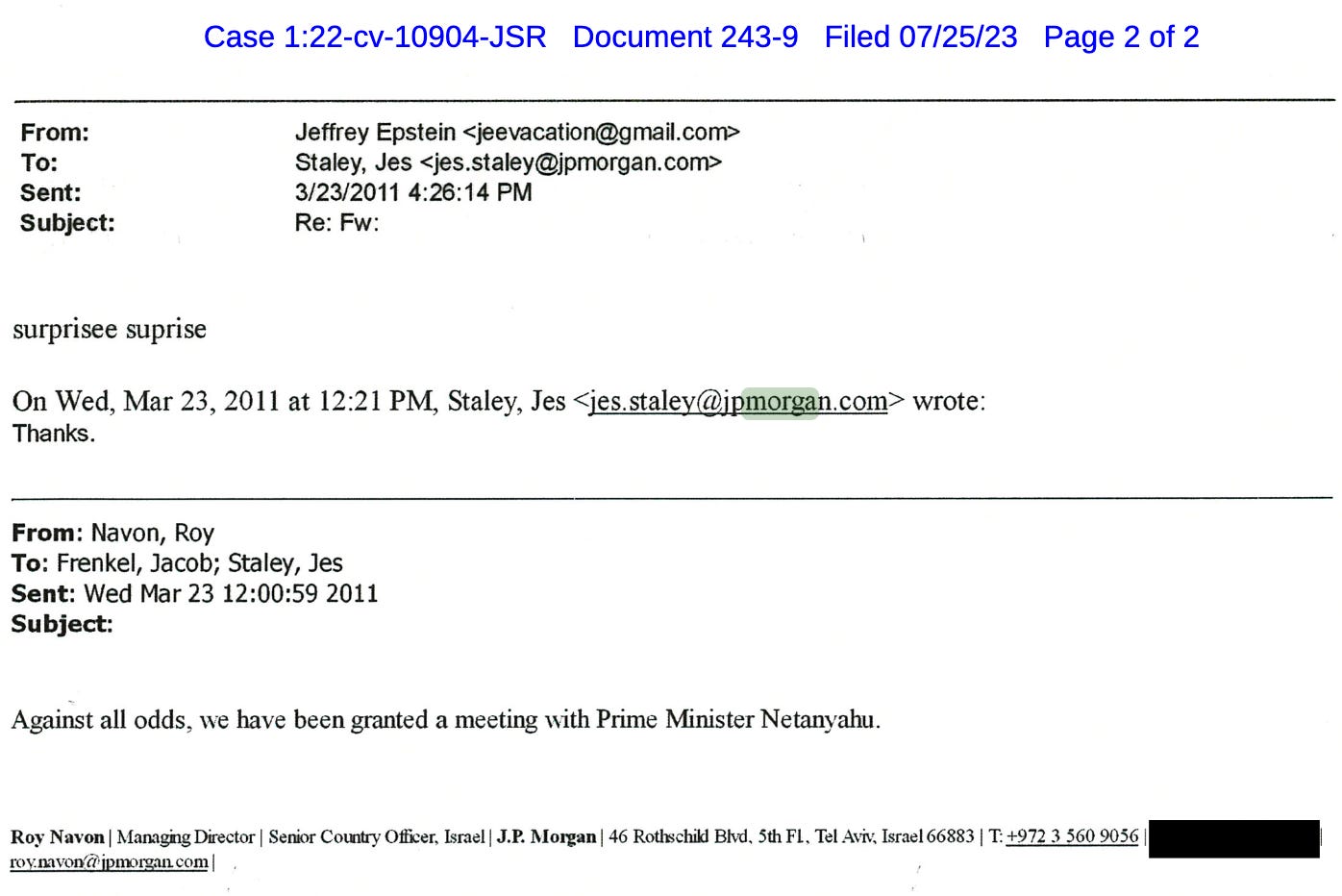

With U.S.-Russia competition in the background, Epstein emailed Barak on August 1, 2013 to advise him about challenges to American investment in the Leviathan field’s development. Netanyahu’s cabinet had decided to allocate 40 percent of its gas reserves for foreign exports, but a judge threatened to halt the decision, due to a pending lawsuit over whether the cabinet had the authority.

Epstein reacted to the news: “Supreme Court President Asher Grunis said on Thursday that he is inclined to issue an injunction banning natural gas export until the court ruled on the matter. im not sure an amercian [sic] energy co, will do well in israel.” Barak replied to Epstein’s warning, “U R probably right but I would like to check it somehow.”

Emails between Epstein and Barak, August 1, 2013.

Epstein and Barak’s private discussions about the future of Leviathan came as Israeli antitrust regulators, faced with the enormous size of the new Leviathan field, were threatening to break up Delek and Noble’s monopoly on Israel’s large gas fields—an outcome the group was eager to get ahead of by enlisting Barak’s help.

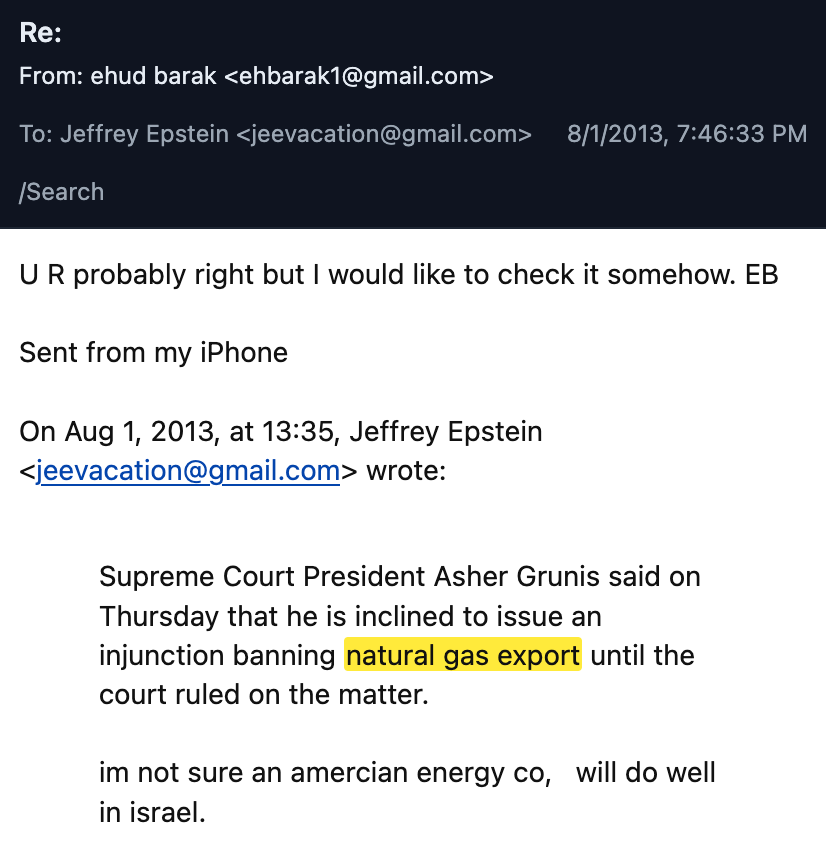

On January 16, 2014, according to a confidential memo written by Barak, Yitzhak Tshuva, the owner of Delek Group, visited Barak’s home to ask for help finding a “major player” to acquire rights to Leviathan production for the Israeli domestic energy market, in anticipation of an anti-monopoly order aimed at breaking up Tshuva’s holdings. The regulator’s concern stemmed from past contracts, from before the Leviathan discovery, that had locked in high prices for Israeli consumers. The same day as Tshuva’s visit, Barak sent an urgent email to Epstein, asking to speak on the phone.

The next day, Barak contacted his associates at Renova Group, the conglomerate owned by Russian-Israeli billionaire Viktor Vekselberg. Barak had a lucrative consulting agreement with Renova to source energy, mining, and real estate opportunities. As Drop Site previously reported, Barak and Epstein had leveraged the relationship with Renova in another strategic initiative for Israel in 2013, a diplomatic backchannel to Vladimir Putin during the Syrian civil war.

In a memo sent to Renova on January 17, 2014, Barak explained that Israel’s anti-monopoly regulator planned to break Tshuva’s control over Israel’s gas by forcing the Leviathan consortium to bring in a new partner for domestic energy supply. “The Problem is that Mr.Tshuva is the major share holder in both Yam Thetis AND Tamar (really a lucky guy),” Barak wrote, referring to two other gas fields controlled by Delek and its partners.

Excerpt of confidential memo from Ehud Barak to Renova Group regarding Leviathan gas field (January 2014).

The full memo is available here:

Leviathan Proposal

57.7KB ∙ PDF file

Barak offered Renova marketing rights to roughly one-eighth of Leviathan’s reserves, but only for domestic sales inside Israel. Renova would also take on the obligation to drill new production wells, build an offshore platform, and lay a dedicated underwater pipeline to shore. The proposal promised long-term contracts to Israel’s largest electric utility, an attractive security for borrowing money.

Renova’s representative, Yakov Tesis, wrote back on January 21, “it makes no sense for Renova to accept the offer,” as Renova would be taking on huge risk to see the project succeed, without any real ownership of the gas reserves. Barak tried to sweeten the deal by showing Renova a memorandum of understanding from Woodside Energy Group, an Australian firm, that valued the field at over $10 billion, but Renova declined again. (Woodside walked away soon after.)

Meanwhile, Barak pursued American private equity interests, in spite of Epstein’s earlier warning. In February of 2014, Barak shopped the Leviathan deal to U.S. private equity giant Texas Pacific Group (TPG), an occasional collaborator with Leon Black’s firm Apollo Global Management. TPG partner Chris Ortega replied that, while the Leviathan discovery was a “transformative” moment in Israel’s energy politics, any solution would be capital-intensive and politically fraught and take too long to see a return on investment.

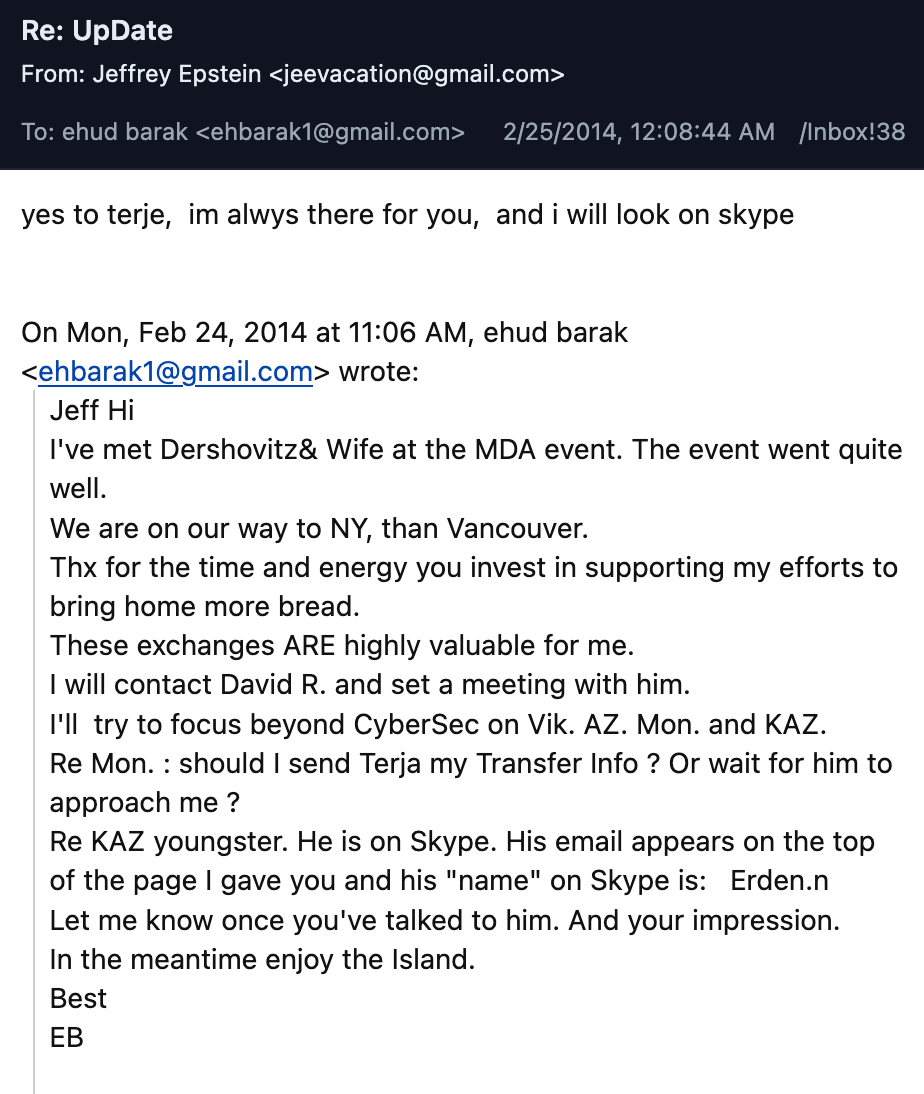

Facing another setback, Barak continued to lean on Epstein for support. After an event for Israel’s national emergency response service in Palm Beach two weeks later, Barak wrote to Epstein, “Thx for the time and energy you invest in supporting my efforts to bring home more bread. These exchanges ARE highly valuable for me.” At the time, the two men had been pursuing funding for offensive and defensive cybersecurity startups sourced from Israeli intelligence, including Carbyne, an emergency response platform founded by alumni of Israel’s Unit 8200 signals intelligence unit.

Now, Barak reported to Epstein that he was ready to broaden the scope of his efforts, writing, “I’ll try to focus beyond CyberSec on Vik. AZ. Mon. and KAZ.” — referring to opportunities with Vekselberg, Azerbaijan, Mongolia, and Kazakhstan. Epstein replied, “im alwys there for you.”

Barak reports to Epstein after a Magen David Adom event; he asks Epstein to call a man from Kazakhstan. February 25, 2014.

In Barak’s confidential memo to Renova, he had outlined a three-fold plan for Israel’s gas exports from Leviathan. First, regional exports to the Palestinian Authority, Jordan, and small amounts to Egypt; second, a gas pipeline to Ceyhan, Turkey for the Turkish market and Europe; and, third, a liquefied natural gas plant in Cyprus to export gas to Asia and the rest of the world.

Barak had begun talks with the leadership of SOCAR, Azerbaijan’s state-owned oil company, to partner with the Delek–Noble group in developing Leviathan. Barak hoped to negotiate access for Israeli gas interests into the Trans Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) and Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), the central and western segments of the Southern Gas Corridor that crossed from Azerbaijan to Italy through Turkey. Avelar, a Swiss-based subsidiary of Renova, operated key gas infrastructure and power utilities in Italy, with alleged links to Italian bureaucrats involved in pipeline politics. Barak pitched SOCAR executives on a deal linking the Leviathan field to the “real power structure” in the TANAP/TAP corridor.

The next month, in March, Barak’s wife sent Epstein their travel itinerary for Rome and Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan. Epstein and Barak made plans to speak on the phone before Barak departed.

Barak gives Elshad Nassirov (VP of SOCAR) an update on Leviathan. Barak had a $6 million per year consulting agreement with SOCAR for “business development.” February 20, 2014.

Epstein, meanwhile, continued to steer Barak’s efforts to establish his reputation as a credible energy dealmaker. As Barak searched for partners for Leviathan, Epstein was not shy about giving harsh criticism to his friend.

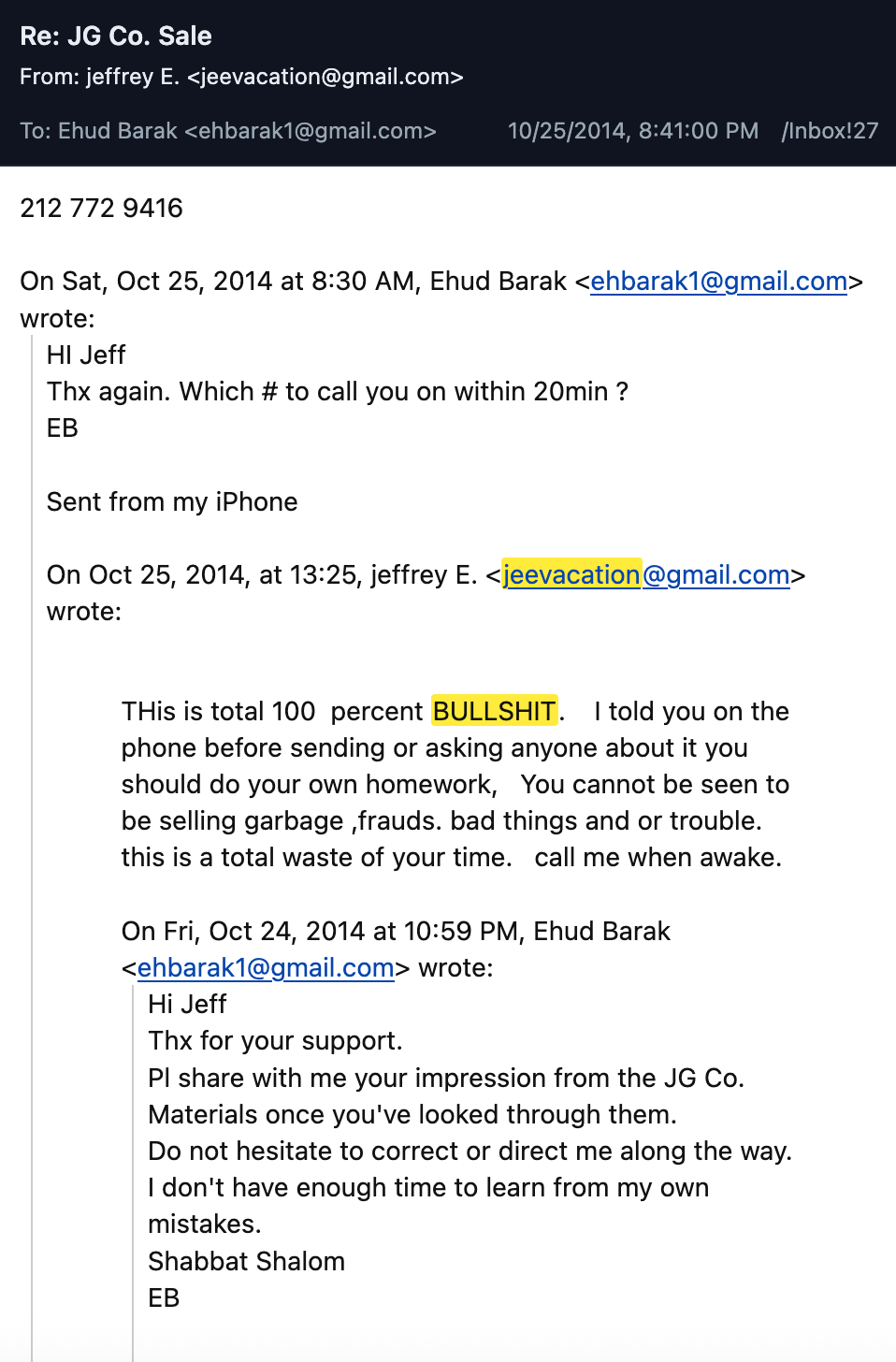

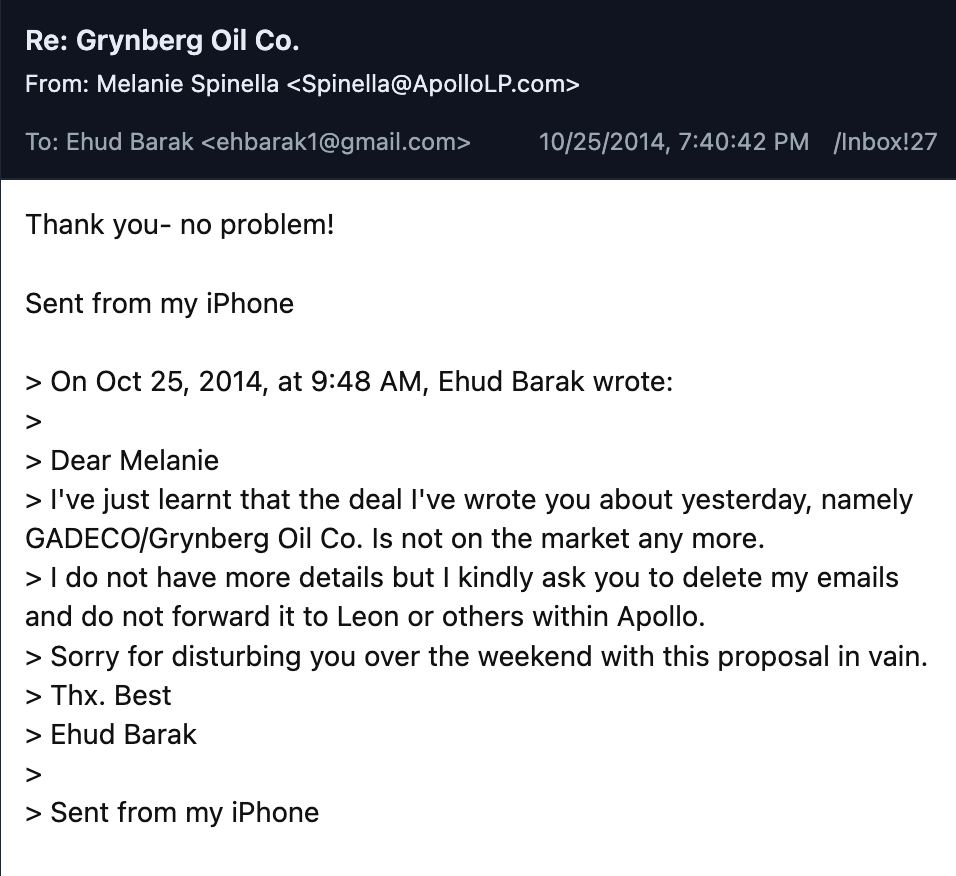

When energy tycoon Jack Grynberg asked Barak to find a buyer for his oil & gas assets, Barak wanted to loop Renova into the deal. But, first, he shared Grynberg’s financial statements with Epstein and Apollo CEO Leon Black for due diligence. Barak wrote to Epstein deferentially, “Do not hesitate to correct or direct me along the way. I don’t have enough time to learn from my own mistakes. Shabbat Shalom.”

A few hours later, Epstein sent a frustrated response: “This is total 100 percent BULLSHIT. I told you on the phone before sending or asking anyone about it you should do your own homework, You cannot be seen to be selling garbage ,frauds. bad things and or trouble. this is a total waste of your time.”

Barak scrambled, sending an email to Black’s executive assistant, “I’ve just learnt that the deal I’ve wrote [sic] you about yesterday, namely GADECO/Grynberg Oil Co. Is not on the market any more. I do not have more details but I kindly ask you to delete my emails and do not forward it to Leon or others within Apollo.”

Emails between Barak and Epstein, October 24-25, 2014.

Email from Barak to an assistant at Apollo, October 25, 2014.

“Stolen Gas”

Barak and Netanyahu, although political rivals, both wanted to see Leviathan succeed. While Barak tried to shop Leviathan access to overseas investors who could absorb Israel’s regulatory chaos, Netanyahu applied a different lever: turning Leviathan into a national security issue that would override anti-monopoly regulations altogether. When Barak failed to protect Tshuva’s gas monopoly by bringing in a compliant foreign partner, Netanyahu used the prime minister’s office as a blunt instrument to restructure Israel’s energy economy.

Shortly after Leviathan’s discovery, in January 2011, Netanyahu warned that offshore gas fields were a “strategic objective that Israel’s enemies will try to undermine” and vowed that “Israel will defend its resources.” By 2014, he had backed a plan for the Israeli government to cover up to half of the security costs for offshore facilities. These were promising signs for money-lenders: in April of 2014, Reuters reported that Tshuva’s company, Delek, was beginning a “road show” to raise up to $2 billion in bonds to fund Leviathan’s development, with underwriting from JPMorgan, Citi, and HSBC. The bond offering closed on May 11.

Just two months later, on July 8, 2014, Israel began “Operation Protective Edge,” a brutal assault on Gaza that killed more than 2,000 Palestinians, the majority of whom were civilians. At the start of the war, IDF officials were reportedly concerned Hamas might use long-range rockets to threaten offshore gas rigs. A blog post for The Guardian argued that control over gas, particularly the Gaza Marine field, was a key driver of Israeli policy. The author, British journalist Nafeez Ahmed, was fired the next day. (According to Ahmed, a Guardian editor justified the decision stating, “Palestine is not an environment story.”)

In his post, Ahmed noted that Israel’s Minister of Defense at the time, Moshe Ya’alon, had argued in a 2007 policy paper that allowing Gaza to develop its own gas would “bankroll terror” by making Hamas rich from gas royalties. Alternatively, if the Palestinian Authority was given control of the gas and Hamas was excluded from gas profits, Ya’alon claimed, Hamas would retaliate by sabotaging Israel and PA gas infrastructure. Ya’alon wrote, “It is clear that without an overall military operation to uproot Hamas control of Gaza, no drilling work can take place without the consent of the radical Islamic movement.”

Gaza’s gas politics impacted Israel’s diplomatic relations with its Arab neighbors; Jordan, like Israel, suffered from energy shortages due to attacks on Egyptian pipelines after Mubarak’s fall. In autumn 2014, Jordanian officials announced plans to import gas from both Gaza Marine and Israel’s Leviathan field.

The Leviathan announcement immediately sparked domestic backlash and street demonstrations against the purchase of “stolen gas.” In early January 2015, Jordanian media reported Amman put the Leviathan talks on hold after Israel’s antitrust regulator moved against the Delek–Noble consortium. Jordanian officials announced they would proceed with plans to buy gas from Gaza.

Amid the fighting in Gaza and protests in Amman, Leviathan was halted. The Leviathan owners, and their financiers, would not sink billions into development without regulatory certainty from the Israeli government. Delek executives threatened international arbitration, and Noble warned it would not invest more until the antitrust dispute was resolved.

Barak pressed forward, looking to Asia for answers. In April of 2015, he exchanged emails about an “energy play” with Joshua Hantman, a former advisor to Israel’s ambassador to the U.S. They discussed a Cyprus-based company called Cynergy Group, which was looking to buy up natural gas assets in the Eastern Mediterranean, including a stake in Leviathan. Hantman reported to Barak confidentially that he had garnered interest from South Korea’s Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister, Choi Kyoung-hwan, as well as members of the president’s office. Hantman wrote, “That is the world’s largest strategic buyer of gas - ready to join us.” Barak wrote back, “Stay in touch and let’s see whether a way to collaborate will emerge.”

Leviathan was by now becoming an explosive political conflict in Israel. That spring, Israel’s antitrust commissioner resigned, warning that Netanyahu’s government was prioritizing monopolists and foreign buyers at the expense of Israeli consumers, who would face higher gas prices if the Delek–Noble monopoly was not broken. Economy Minister Aryeh Deri also resigned, under pressure from Netanyahu to exempt the gas framework from antitrust scrutiny. Netanyahu, still the prime minister, stepped in to take over Deri’s economy portfolio.

Then, in September, the Russian military officially entered the Syrian civil war, launching airstrikes across Syria in support of Bashar al-Assad’s regime. With extraordinary leverage, Russian President Vladimir Putin reportedly offered Netanyahu a deal: Give Gazprom a stake in Leviathan, and, in exchange, Russia would protect the gas fields from Hezbollah and Hamas. Now, the debate in Israel had a new dimension: accepting Gazprom would resolve the deadlock, guarantee the gas field’s security, and instantly turn Israel into an indispensable energy exporter—at the cost of alienating Israel’s allies in the U.S. and Europe.

Netanyahu found an opportunity, in one blow, to appease Israel’s neighbors, its NATO allies, and the gas oligarchs at home. In December 2015, after months of Knesset clashes, Netanyahu used an obscure section of the country’s antitrust law to authorize the economy minister (now Netanyahu himself) to permit a gas monopoly on national security grounds. Netanyahu invoked relations with Jordan, Turkey, and Europe to justify the move, signaling to banks and allies that Leviathan was politically protected.

“Fake News”

After Netanyahu’s move to break the Leviathan deadlock, Amman quietly resumed planning to import gas from Leviathan. In September 2016, Jordan signed a $10 billion deal to import gas from the field, spurring a resumption of protests under the slogan “The Enemy’s Gas is Occupation.” Jordanian officials sealed the Leviathan contract under “state secrets” rules and waited out the protests.

Soon after, in November of 2016, the Delek–Noble consortium announced it had secured a $1.75 billion loan from JPMorgan and HSBC for the first phase of Leviathan’s development. The framework that made JPMorgan financing possible transformed Israel’s gas sector into a protected duopoly. Under Netanyahu’s gas framework, Tshuva and his partners retained control of Leviathan, which would become Israel’s main gas export supply, but were forced to sell their stake in the smaller Tamar field—leaving Isramco (linked to Kobi Maimon) as the controlling owner of Israel’s main domestic gas supply.

Egypt followed a similar pattern to Jordan: quiet diplomacy, private contracts, and plausible deniability. In 2018, a Cairo-based buyer signed long-term “private-sector” purchase agreements for Tamar and Leviathan gas, and the Leviathan partners bought into the dormant Mubarak-era pipeline that once sent Egyptian gas to Israel, so it could be reversed for exports.

The first gas from Leviathan finally began flowing in December 2019. A small amount of this early gas flowed to Egypt through the reversed pipeline.

Leviathan gas field. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Earlier that year, on June 26, 2019, Barak announced his intention to challenge Netanyahu in an election slated for that September. Two days later, emails from Epstein’s estate show Epstein messaging Steve Bannon about the election and “dealing with Ehud in Israel.” Bannon praised the decision and asked Epstein whether he could announce himself as Barak’s strategic advisor.

Epstein did not live to see the vote—he died in a Manhattan prison cell on August 10, 2019. Despite his death, Epstein’s ghost continues to haunt Israeli politics. In November of 2025, Netanyahu posted, without comment, an article from Jacobin magazine containing Drop Site’s reporting on Epstein’s ties to Barak and Israeli intelligence—implicitly leveraging Epstein’s connection to Barak to detract from his longstanding rival.

Netanyahu now openly invokes Epstein to wound Barak, using Epstein’s crimes to deflect attention from his own corruption cases and his responsibility for the genocide in Gaza. “The media channels are not news channels, they are fake channels,” he said in March, “They invite Ehud Barak again and again… with great respect and dignity, but, strangely, he is not asked a single question on [Epstein].”

From Drop Site News via This RSS Feed.