Chomsky’s claim to fame in his primary field of linguistics came from his 1957 publication Syntactic Structures, a monograph extracted from his dissertation. The main proposal was for an all encompassing linguistic theory, whereby Chomsky defines language as:

All natural languages in their spoken or written form are languages in this sense, since each natural language has a finite number of phonemes (or letters in its alphabet), and each sentence is representable as a finite sequence of these phonemes (or letters), though there are infinitely many sentences.1

The main contribution of Syntactic Structures is the proposal to study syntax as an autonomous formal system, separate from meaning. Chomsky introduces the idea of a generative grammar, defined as a finite set of rules capable of generating all grammatical sentences of a language while excluding ungrammatical ones. At the time, linguistic analysis relied heavily on phrase structure rules, such as representing a sentence as a noun phrase plus a verb phrase. Chomsky accepts these rules as a starting point but argues that they are insufficient on their own. He proposed transformations that derive non-kernel sentences from a basic set of kernel sentences, capturing systematic relationships among sentence forms without redundancy. The most controversial aspect of this approach is the claim that syntactic well-formedness cannot be reduced to semantic meaningfulness, illustrated by the famous sentence “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously,” which is grammatically well formed despite being semantically anomalous.

Historic.ly is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

This methodological separation of syntax from meaning generated controversy within the broader social sciences, as it deliberately abstracted away from the historical, social, and political dimensions of language. In Syntactic Structures, a language is defined purely as a formal set of sentences generated by a grammar, and communication between speakers is not part of the definition. These factors are bracketed in order to focus exclusively on the formal properties of syntactic structure

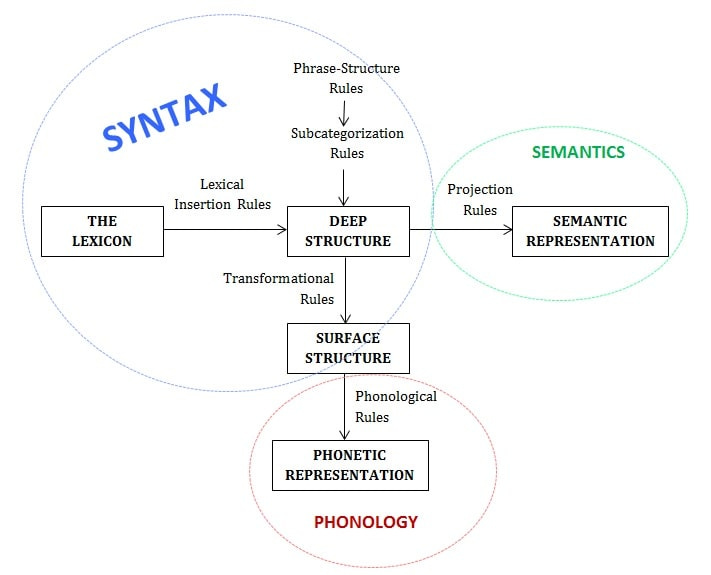

Chomsky’s next book, Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (1965), systematized and extended the framework sketched in Syntactic Structures by proposing a fully articulated theoretical architecture for linguistic competence, later known as Standard Theory. As we mentioned earlier, he abstracts away any actual speakers as “performance” and instead focuses on the competence of an “ideal speaker-listener.” In fact, the actual question he attempted to answer was, how a child could learn a language despite having listened to “imperfect speakers” or actual people. He states:

To learn a language, then, the child must have a method for devising an appropriate grammar, given primary linguistic data. As a precondition for language learning, he must possess, first, a linguistic theory that specifies the form of the grammar of a possible human language, and, second, a strategy for selecting a grammar of the appropriate form that is compatible with the primary linguistic data2

The details are tedious, but the principle is clear: language is formalized as a nested hierarchy of representations, in which meaning is fixed early and progressively insulated from use. As Chomsky puts it, “the syntactic component of a grammar must specify, for each sentence, a deep structure that determines its semantic interpretation and a surface structure that determines its phonetic interpretation.”3 Meaning, once assigned, is no longer negotiated in discourse but carried through successive layers of structural manipulation.

For those who want to give a charitable reading to Chomsky, and claim that he is proposing a model for machine that take human speech as input are wrong… In Aspects of the Theory of Syntax, Chomsky, he explicitly frames linguistic theory as a theory of mental competence, describing the internalized knowledge that an ideal speaker-hearer possesses, rather than an account of performance, behavior, or engineering systems4

The biological community rightfully criticized Chomsky for not incorporating any data on actual language acquisition, the anthropological community criticized him for ignoring the cultural aspect of language as a group activity, where communication is primary. The one field that met Chomsky’s proposal enthusiastically was the computer science community, who thought it could be useful for creating a computational linguistic machine.

However, two mathematicians R. Stanley Peters and Robert Ritchie dashed his hopes when in 1973, they proved Standard theory to be Turing-complete.5meaning it could generate any recursively enumerable set, not just human languages. The theory had become so powerful it could no longer distinguish between actual human language and arbitrary strings of symbols. A linguistic theory that can generate anything at all is scientifically useless: it makes no falsifiable predictions about what counts as a possible human language versus what doesn’t. As one sharp-tongued critic put it, Chomsky’s model was about as useful as "a biological theory which failed to characterize the difference between raccoons and light bulbs."6 If your theory of biology can’t tell living organisms from inanimate objects, it’s not a theory of biology—and if your theory of language can’t distinguish language from non-language, it’s not a theory of language. Consequently, computer scientists abandoned the formalism entirely and turned to statistical methods for natural language processing.

Despite these evidentiary setbacks, Chomsky never abandoned his initial assumptions about language. He instead came out with yet another theory known as Government and Binding in 1981 and most importantly in the 1980s, he posited an idea of Universal Grammar (UG) that answered questions based on a set of flawed assumptions that do not conform to actual data:

(1) removed,Meagre, and Minute Language Input, (2) Impoverished Stimulus Input, (3) Ease and Speed of Child Language Acquisition, and (4) The Irrelevance of Intelligence in Language Learning.

He defined UG as a

Universal Grammar is defined as the core grammar containing the principles and parameters which apply to all languages. The other aspects of th e grammar of any particular language are referred to as ‘peripheral grammar’ and a ‘mentallexicon’. These must be learned separately from UG because the peripheral grammar and the lexicon are not universal but are specific to particular languages7

Furthermore, Chomsky makes a distinction between E-language (external language and communication that we use in our speech) and I-language (internal language for cognition). He posits that UG is meant to explain only I-language, once again echoing his “competence vs performance” split from earlier. In fact, an anything that is uncomfortable or disproves his theory can always be moved to the category of e-language.

His UG theory was shown not to conform with any empirical data, as all the initial assumptions were proven false. The inputs are not removed. There is no impoverished stimulus, children take 4-5 years to learn languages and intelligence is not a well defined biological category. (See Psycholinguistics for an entire Chapter Debunking UG)

As UG became more and more cumbersome, Chomsky decided, once again to change his theory called the “minimalist program” in 1995. He stripped away much of the elaborate technical machinery—the complex transformational rules, the Government and Binding parameters—but retained all the core assumptions: language is innate, biologically specified, autonomous from meaning and social context, and governed by Universal Grammar.

What changed was the claim about what Universal Grammar actually is. After decades of failed predictions, Chomsky reduced it to a single essential property: recursion—the ability to embed structures within structures infinitely, like in the children’s song “There Was an Old Lady Who Swallowed a Fly”: she swallowed a spider to catch the fly, then a bird to catch the spider (that wiggled and jiggled inside her to catch the fly), then a cat to catch the bird (to catch the spider to catch the fly)—each verse embedding all the previous ones.

This, he now claimed, was the defining feature separating human language from all other communication systems. Everything else could vary, but recursion was the irreducible universal core.

But when linguists actually examined languages across the world, they found counterexamples. Pirahã, an Amazonian language documented extensively by Daniel Everett, appears to function perfectly well without Chomskyan recursion. The language has no embedding, no relative clauses, no recursive structures of the type Chomsky claimed were universal—yet its speakers communicate complex ideas successfully.

Members of the Piraha community, whose language debunks Chomsky’s theories

Chomsky’s linguistic theories, from Universal Grammar to the Minimalist Program, are founded on a decisive—and fatal—move: they define their object of study as an internal computational system, explicitly excluding its communicative function. By relegating social use, meaning negotiation, and pragmatic context to the periphery of ‘performance,’ the theory renders itself irrelevant to explaining why language exists, how it is learned in interactive contexts, and how it shapes and is shaped by society. It is a meticulous blueprint for a machine that is never plugged in, a formalist fantasy that, by its own design, cannot engage with the core reality of language as a tool for human connection and control. In excluding communication, it excludes everything that makes language, a system of communication.

In other words, his theory of languages are “colorless green ideas” or entirely nonsensical sentences that have no bearing to language acquisition to human or machine learning.

For Chomsky, the only scientifically legitimate object of study is the internal, individual cognitive system—the I-language generated by the biological blueprint of UG. Everything else, particularly the messy external collectivities we call ‘English’ or ‘French,’ is derivative and ‘obscure.’ This intellectual move is not merely technical; it is profoundly ideological. It establishes a foundational principle that he will apply relentlessly in his political work: that true understanding comes from analyzing the inherent capacities and rights of the individual (the ‘I-state’), while dismissing larger collective structures—be they languages, states, or historical traditions—as arbitrary, obscure, and ultimately illegitimate constraints on human freedom. In essence, his linguistics provides the epistemological blueprint for his anarchism.

Part 2: The Acceptable Dissident

Noam Chomsky, Syntactic Structures (The Hague: Mouton, 1957), 13.

Noam Chomsky, Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1965), 25.

Ibid at 16.

Ibid 3-5

Stanley Peters and Robert W. Ritchie, “On the Generative Power of Transformational Grammars,” Information Sciences 6 (1973): 49–83.

Christopher Knight, Decoding Chomsky: (London: Pluto Press, 2015), chap. 2.

Danny D. Steinberg, Hiroshi Nagata, and David P. Aline, Psycholinguistics: Language, Mind and World, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 2001), 294

From Historic.ly via This RSS Feed.