MANILA – Right after the police and military raided their boarding house, Manobo indigenous activist Julieta Gomez can still vividly remember when they were paraded as “communist-terrorists” inside the Criminal Investigation and Detection Group (CIDG).

“Arresting indigenous peoples and activists like me was easy for them– even to the point of planting evidence,” Gomez told Bulatlat in an interview. “But those implicated in the corruption, even with the presence of clear evidence, continue to run free.”

Gomez and indigenous rights activist Niezel Velasco were illegally arrested on July 16, 2021, in a joint military and police operation. They were charged with murder, attempted murder, and illegal possession of firearms and explosives, which were dismissed by the Quezon City Regional Trial Court (RTC) Branch 91 on April 8, 2025.

Prior to their arrest, the two indigenous rights activists flew to Manila to campaign for justice for the second Lianga Massacre, killing three Lumad-Manobo individuals, including a 12-year-old girl on June 15, 2021, in Sitio Panukmoan, Liangga, Surigao del Sur.

Read: 2 Lumad farmers, 1 student killed in another Lianga massacre

Gomez said the circumstances of their arrest remain etched: state agents forcing their way into the house in the pre-dawn hours blowing the doors open, two guns aimed at their heads as they were ordered outside. Just as troubling, Gomez recalled, was the sudden empty black bag: once full of materials with the sound of heavy metal. When the state agents ordered them back to their boarding house, 40 minutes after staying outside, the police presented what they claimed to have “recovered” – firearms, explosives, and paraphernalia.

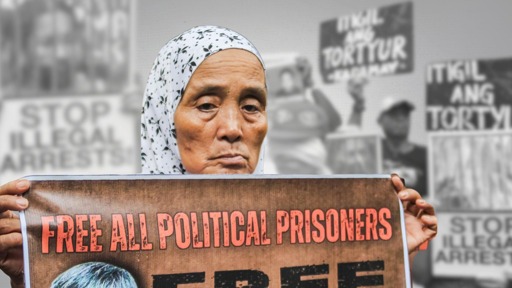

Now, the two are fighting back by filing countercharges against the police officials responsible for their arrest at the Office of the Ombudsman. But their case is emblematic of the common pattern of politically-motivated charges against activists – over 700 political prisoners languish in the repeated patterns of illegal possession of firearms and explosives, or the twin-terror laws, or both at the same time.

The terror against dissenters, marginalized

“The political prisoners were the ones who stood in the line of fire against the struggle against corruption and the struggle for justice, freedom and national democracy,” martial law survivor and former political prisoner Bonifacio Ilagan, who also represented the Samahan ng mga Ex-Detainees Laban sa Detensyon at Aresto (SELDA), said in a press conference on December 1.

There are a total of 696 political prisoners based on the joint monitoring of SELDA and human rights group Karapatan. Of these numbers, 93 are elderly, 136 are women, 89 are sick, 12 are consultants and staff of the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP) who should be protected under the Joint Agreement on Safety and Immunity Guarantees (JASIG), an agreement signed by the Philippine government and the National Democratic Front of the Philippines in 1995.

Ilagan added, “they are the ones who should be given freedom on the basis of humanitarian reasons, not the likes of Duterte.”

In a protest at the Department of Justice last December 3, SELDA spokesperson and former political prisoner Adora Faye de Vera said, “Most political prisoners are peasant and labor organizers, human rights defenders, development workers and even ordinary citizens slapped by the DOJ with trumped-up criminal cases on mere suspicion of supporting the revolutionary movement.”

She added that the twin terror laws — Anti-Terror Act (ATA) and the Terrorism Financing Prevention and Suppression Act (TFPSA) have been increasingly used by the DOJ against dissenters. Karapatan reported that at least 30 of those charged with violating the twin terror laws are still detained.

“There is rank injustice in targeting those who fight corruption and advance human rights,” said Karapatan deputy secretary general Maria Sol Taule, “but turning a blind eye to the biggest plunderers and fascists like Marcos Jr. and his ilk.”

Attacks on anti-corruption dissenters

Meanwhile, not one has been held fully accountable in the blatant corruption scandal, not even with the establishment of the Independent Commission for Infrastructure (ICI), whose investigations are still ongoing.

Bulatlat’s monitoring recorded that most of the high officials implicated in the flood control corruption scandal denied the allegation, resigned from their posts or left the country, while others were invited to hearings. Among those investigated by the Office of the Ombudsman are former and present politicians implicated by former DPWH undersecretary Roberto Bernardo but the public sees no immediate consequences or follow-through of most of these investigations after the denial.

The same pace of progress goes for the public officials and private entities facing charges before the Ombudsman.

Most of the lawmakers named by the Discaya couple in their affidavit were not subjected to further official investigation after being invited to the Blue Ribbon committee hearings. The sheer volume of individuals linked and indicted constitutes no real accountability emerging from the investigations.

On the other hand, attacks against anti-corruption dissenters have been persistent. According to Mark Vincent Lim, one of the lawyers who responded to the mass arrests during the September 21 protest, there have been 216 victims of unlawful arrest, including 91 minors, and two people died: worker Eric Saber who happened to be a bystander and an unidentified man killed by a stab wound.

“As far as I know, most have already been released on bail,” Lim told Bulatlat. Most of the people arrested are charged with Tumults and Other Disturbances of Public Order (153), while the initial charges for Illegal Assembly and Direct Assault are dismissed by the Manila prosecutor due to insufficiency of evidence.

Most of them have been detained without warrant for more than three days, which is beyond the period allowed by the Revised Penal Code.

Moreover, the Criminal Investigation and Detection Group (CIDG) is going after student leaders from Polytechnic University of the Philippines and University of the Philippines who joined the protest, issuing subpoenas.

In the November 30 protest, three individuals were arrested and shortly released without charges.

Rights violations and resistance inside jails

Meanwhile inside prison, rights of political prisoners and other persons deprived of liberty (PDL) continue to be violated. Gomez said that during their detention, the prison warden in Camp Karingal isolated them from the rest of PDLs.

“We were padlocked in a small room as big as two in a half arm-spans – all three political prisoners – for the majority of detention there in more than two years,” Gomez added. Written outside their room were words: high-ranking communist-terrorists. “We ask them to remove the texts– asserting to them that what they are doing are human rights violations.”

In Negros, political prisoners and other PDLs held hunger strike against the degrading treatment inside the facilities. Karapatan reported that in Negros Occidental District Jail (NODJ), both PDL and political prisoners endure rights violations, arbitrary punishment, and humiliation. The authorities label the political prisoners as members of the “communist terrorist group,” subjecting them to further harassment and punitive measures.

Read: Detainees hold hunger strike due to inhumane treatment

Human rights groups called on the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP) National Headquarters and the Commission on Human Rights to conduct a full, impartial, and urgent investigation into the controversial reinstatement of NODJ Warden Crisyrel Awe. They also demand the immediate ending of harassment, unlawful isolation, intimidation, restricted visits, and suppression of rehabilitation programs.

“These acts deepen fear, sustain injustice, and portray PDLs as criminals rather than human beings with inherent dignity,” said Karapatan in a statement.

The group also underscored that the hunger strike exposes the structural injustice in the Philippine penal system, “where the poorest workers, farmers, and urban poor fill overcrowded jails, while the wealthy, corrupt, and powerful evade accountability.”

Congestion in the Philippine jails remains extremely high. The average congestion rate as of May 2025 is almost 300 percent. This overcrowding causes various humanitarian consequences.

The International Committee on Red Cross (ICRC) noted that overcrowding means persons deprived of liberties have limited movement, sleeping spaces, and ventilation. This also means inadequate access to water, sanitary facilities and healthcare– causing disease-causing bacteria and viruses to spread faster.

In the 2025 General Appropriations Act (GAA), there is a total of P4.6 billion for subsistence and almost P1 billion for medical allowance for 182,556 PDLs. This amounts to almost P70 for food and P15 for medical expenses of every PDL. This has been a static budget for PDLs in the last five years.

International solidarity and rights instruments

Three United Nations experts — Mary Lawlor, on the situation of human rights defenders; Gina Romero, on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association; and, Michel Forst, on environmental defenders — signed a collective statement, calling out the global trend of prolonged pretrial detention and long-term imprisonment of human rights defenders.

“Arbitrary detention remains one of the most common and cruel tools used by repressive authorities to silence those peacefully exercising the right to defend human rights and to dismantle civil society,” the statement read.

Read: Double standards in the Philippine’s justice system

The statement also emphasized that such actions foster a climate of fear, creating a profound deterrent effect that discourages the legitimate and essential work of activists, human rights defenders, as well as citizens.

The actions violate the international human rights obligations of the UN state parties like the Philippines on Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.

Moreover, Karapatan stated that the punitive actions against political prisoners and PDLs violate the UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (2015 Nelson Mandela Rules), two domestic laws — Republic Act 7438 (Rights of Persons Arrested, Detained, or Under Custodial Investigation) and Republic Act 9745 (Anti-Torture Act), and the own comprehensive operations manual of the BJMP, 2015 edition.

“The existence of political prisoners is a brutal reminder of the oppressive regime Filipinos are facing,” the International Coalition for Human Rights in the Philippines (ICHRP) stated. “The Marcos Jr. administration claims to seek peace, but in reality, it targets and silences those who are fighting for a just and lasting peace.”

The international group joined the campaign to free all political prisoners in the Philippines and demand an end to illegal arrests and detention.

Political prisoners are detained primarily for their political beliefs or activities or perceived involvement in political movements. The motivation behind the arrest is political, regardless of the charges used against them.

“This misuse and abuse of power destroys lives, livelihoods, families and communities. It stifles and inhibits defenders from carrying out their legitimate and essential work, and discourages others from exercising the right to defend human rights,” the UN experts added in the statement. (With reports from Ruth Nacional) RVO

The post Political prisoners languish in overcrowded jails, a stark irony in corruption impunity appeared first on Bulatlat.

From Bulatlat via This RSS Feed.