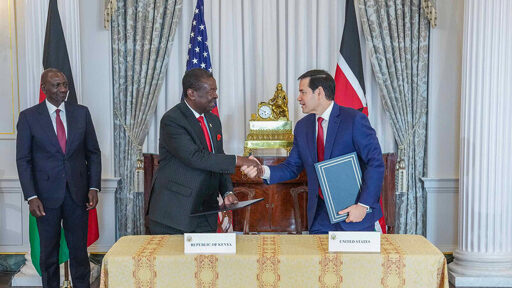

On December 4, Kenya became the first African country to sign a Health Cooperation Framework with the second Trump administration, marking a new phase of US involvement in global health governance. The five-year agreement, worth approximately USD 2.5 billion, falls under the America First Global Health Strategy and is intended to replace previous aid mechanisms while openly prioritizing US strategic interests in health cooperation.

Just one week later, a Kenyan court ordered the suspension of the framework implementation over concerns related to data security. It remains unclear whether the ruling will have immediate practical effects. Meanwhile, the US government has already announced similar bilateral agreements with Rwanda, Lesotho, Liberia, Uganda, and Swaziland.

In response, health activists raised the alarm over the agreements’ content and broader implications. They warn that the documents undermine efforts by African countries to assert health sovereignty and advance their collective interests in multilateral negotiations. “Bilateral agreements between the US and Kenya and other African countries are meant to limit the ability of any one ‘partner’ country to challenge the terms of implementing the agreement, due to the unequal power relations,” activists from the People’s Health Movement (PHM) East and South Africa region told People’s Health Dispatch.

Pathogen access and benefit sharing for the US and Big Pharma, not Africa

More than 50 civil society organizations published an appeal urging African governments not to follow the same path. The agreements, they argue, “dictate US terms that are not guided by African national or regional interests.” Signatories – including PHM Kenya – highlight the long-term nature of certain clauses, particularly those granting access to national data systems and other information for up to decades to come. Such commitments, they warn, could prevent countries from strengthening their own health systems despite official claims to the contrary. “Binding commitments that extend for decades, combined with termination clauses that require US approval, risk creating structural dependence on foreign digital health infrastructure, software, and surveillance systems,” says Dan Owalla of PHM Kenya.

A key concern in the discussion is pathogen and data sharing. Kenya’s framework indicates that signatory countries might be required to provide specimens, samples, and epidemiological data related to potential epidemic or pandemic threats. The US would then be permitted to share this information with third parties, including pharmaceutical corporations. While in this scenario Big Pharma companies would be free to develop medicines and technologies using African data, there is no guarantee that the resulting benefits would be shared equitably, the civil society letter warns. “The danger of a repetition of the COVID-19 saga, when Africa was ‘last in line’ to receive medical tools developed from African data, is real,” the letter states. “This runs directly counter to Africa’s push for regional manufacturing and deeper self-reliance. It also risks locking African producers out of value chains built on African data.”

Such bilateral commitments contradict the position taken by African countries in negotiations related to the Pandemic Treaty, where the 47-state group has been pushing for a more equitable Pathogen Access and Benefit Sharing (PABS) system. They have insisted that medical resources and technologies developed thanks to shared data should be distributed fairly. “By agreeing to one-sided bilateral pathogen sharing agreements with the US, your country risks breaking solidarity with broader African and Global South negotiating blocs, disrupting negotiations toward an equitable system for pathogen and benefit sharing, and fragmenting arrangements for pandemic preparedness and response that are needed to keep everyone safe,” organizations warned African leaders.

Making space for the private sector

Concerns extend beyond pathogens sharing. Activists emphasize that the frameworks could grant US authorities access to personal medical records and allow them to influence national health priorities, particularly by restricting how funding can be used. “Allowing direct US access to Kenyan health records and national data systems could immediately disrupt service delivery, privacy, and resource distribution,” Owalla cautions. “With access to electronic medical records, the US could influence Kenya’s health priorities to suit its own strategic interests, potentially diverting focus from maternal health, non-communicable diseases, primary care, or underfunded county-level services.”

Read more: Structural adjustment by any other name: International Financial Institutions and health in Ghana and Kenya

Activists also point to less explicit implications. “The likely push behind this and other agreements is to privatize the health sector even further, which is not explicit in the arrangement but follows from other US government demands on foreign countries,” PHM East and South Africa activists emphasize.

That the private sector will be a factor in the implementation of the frameworks is evident in US government communications. When announcing the Rwanda agreement – valued at USD 228 million – the US Department of State pointed out the role of American companies Zipline International and Ginkgo Bioworks. According to the announcement, USD 10 million will be allocated to Ginkgo Bioworks alone, “to expand their disease outbreak surveillance in Rwanda, which establishes a biothreat radar system that will help monitor potential outbreaks in the broader region.”

“The arrangement also outlines several health areas where Rwanda is interested in additional US private sector partnership and investment including developing next generation HIV treatments and deploying artificial intelligence (AI) for healthcare,” the statement adds – bringing the discussion full circle by linking data and pathogen sharing, pandemic surveillance, and private sector involvement.

With additional bilateral agreements expected in the coming period, health organizations are urging governments to remain alert to the dangers posed. “There is an urgent need to stand up to US demands and ensure agreements are balanced, including by broadening civil society participation and offering counterproposals to US terms that may be extractive or harmful,” they wrote.

People’s Health Dispatch is a fortnightly bulletin published by the People’s Health Movement and Peoples Dispatch*. For more articles and to subscribe to People’s Health Dispatch, click* here.

The post America First Global Health Strategy: a framework for co-opting healthcare in Africa? appeared first on Peoples Dispatch.

From Peoples Dispatch via This RSS Feed.