Drop Site is a reader-funded, independent news outlet. Without your support, we can’t operate. Please consider making a 501©(3) tax-deductible donation today.

Three armed Israeli settlers use their phones in Tarqumiyah, northwest of Hebron, in the occupied West Bank, on November 28, 2025. (Photo by Mosab Shawer / Middle East Images / AFP via Getty Images)

Story by David Schutz

IBSIQ, WEST BANK—On July 20, around ten masked men raided the Palestinian hamlet of Ibsiq in the northern Jordan Valley in the occupied West Bank. They arrived in a two car convoy, dressed in Israeli military-issue fatigues, and carried assault rifles fitted with green laser pointers.

While their vehicles blocked the road, they stormed into a cluster of homes. At gunpoint, they forced a Palestinian family to their knees and warned them they had 48 hours to evacuate Area C and go to Area B—referring to technical designations of control in the West Bank under the Oslo Accords. Area C is under full Israeli control and Area B is technically under Palestinian civil administration but shares security control with Israel. The masked men said they would “return and burn the community down,” if the family did not evacuate to Area B.

I had been staying with an elderly Palestinian couple for five days in Ibsiq to document settler violence amid rising threats against the community. As the men approached, I asked one of them who he was. They looked like soldiers, but the vehicles in which they arrived had yellow civilian license plates. These masked assailants were members of the hagmar— settler reservist militias formally attached to the Israeli army and tasked with “security” in West Bank settlements.

The men dragged me behind a fence where four of them beat me until I required hospitalization. They stole the phone of an International Solidarity Mission activist who tried to record the attack.

My host, Abu Safi, who was 84, had little choice but to leave his home after that raid by the hagmar. The family packed up their belongings accumulated over decades in the house and moved to a nearby location in Area B. Abu Safi died of a heart attack soon afterwards.

The raid on Ibsiq, whose Palestinian residents have since all fled the depopulated hamlet, offers a glimpse into an essential part of how Israel rules the West Bank.

In parallel with Israel’s genocidal assault on Gaza that began in October 2023, Israeli violence from settlers and soldiers in the West Bank escalated to record levels. About 3,000 settler-related attacks causing Palestinian casualties or property damage were recorded between October 2023 and mid-2025, with more than 1,000 of them in the first 8 months of 2025, and 264 incidents in October 2025 alone—the highest monthly total since the UN began monitoring in 2006.

Over the past two years, settlers have increasingly been “going into houses, holding people at gunpoint, and giving them 24 hours to leave, and many have…It happened in Khirbet al-Maktal, Umm Salam, Razeem, and elsewhere,” Nasser Nawaja, a field researcher with Israeli human rights group B’Tselem, told Drop Site News. “We file complaints, but many times the authorities tell us the perpetrators were acting outside their capacity as soldiers, so we’re referred to the police,” Nawaja added. “Then the police say it’s a military matter. We end up in a situation where no one investigates.”

An Integrated Web of Civilians and Soldiers

Settler violence against Palestinians often appears sporadic, but it is an official government system with an organized structure operating as intended.

Since 1967, Israel has ruled occupied Palestinian territories through dual structures—military occupation and civilian settlements—each reinforcing the other while mutually devolving responsibility.

At the heart of this arrangement lies a legal device: regional settlement councils, chartered under the 1964 Municipalities Ordinance as standard Israeli municipalities, yet which operate in occupied Palestinian territory. Israeli jurisdiction rests on military orders and the West Bank Emergency Regulations, which extend most aspects of Israeli law in personam to settlers but not to the land itself. Territorial authority is supplied by the Israeli military, making the army the de facto sovereign.

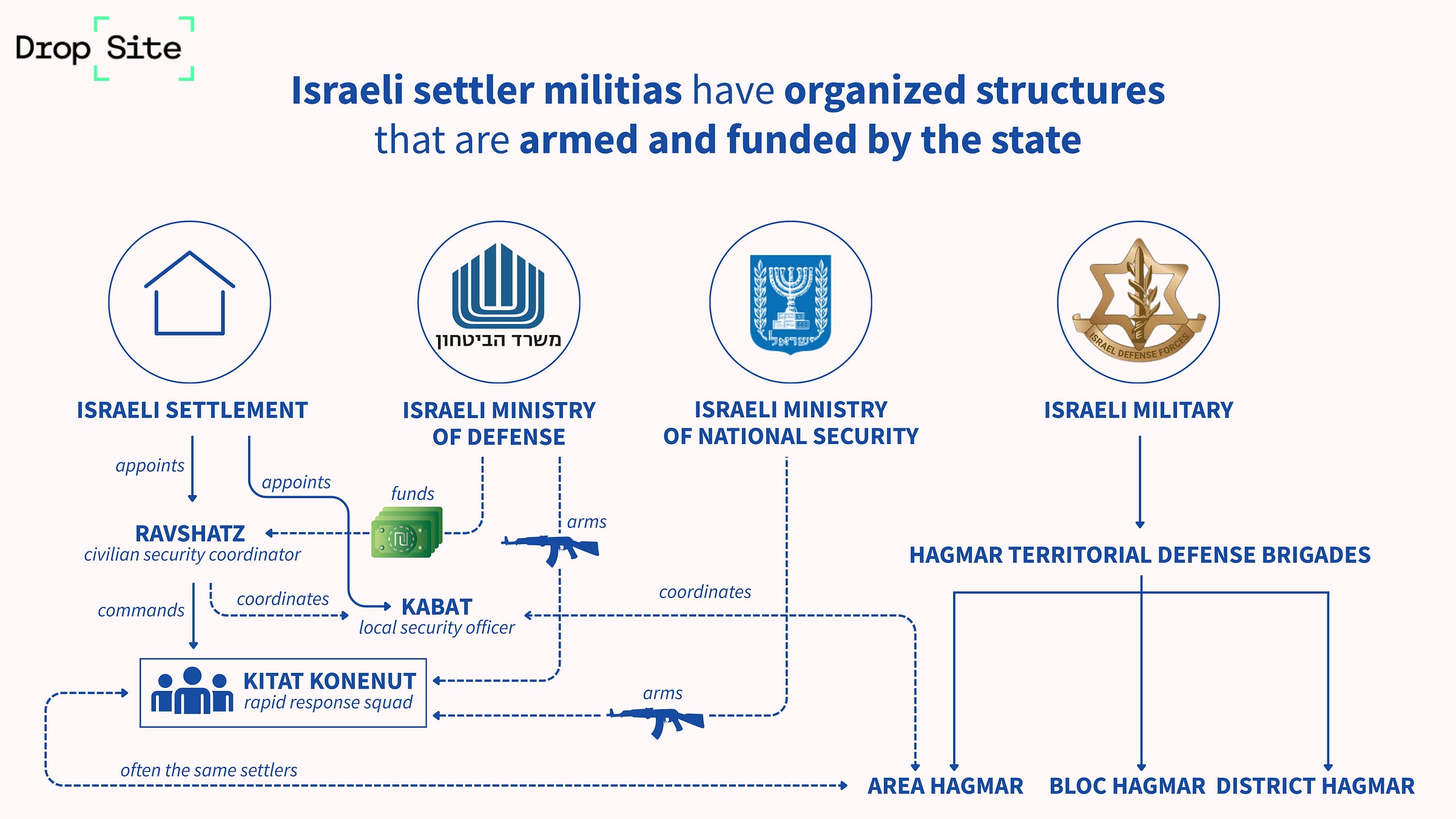

Within this framework, the state delegates enforcement to settlers. Each settlement appoints a ravshatz, or a civilian security coordinator, paid by the Defense Ministry and authorized by the military to command a plain clothes rapid-response squad, or kitat konenut, of 20 to 40 volunteers within the settlement boundary. Weapons are issued from the Defense Ministry’s Department for Settlement Security; additional arms also flow from the National Security Ministry.

Inside Israel proper, these squads fall under police authority. Beyond it, across the military’s sector that covers rural border areas and all West Bank settlements, the ravshatzusually operates through a local security officer, or kabat, who is appointed by the settlement council to coordinate with the army.

Parallel to the ravshatz are the Hagmar Territorial Defense brigades: a reserve network integrating each settlement into a military grid broken out into districts, blocs, and areas. At the two top levels—district and bloc—the hagmar report to the regional hagmar command of the IDF. At the lowest level, the area hagmar corresponds to a single settlement. Each settlement coordinates with its area hagmar through its appointed kabat.

The hagmar are issued uniforms by the IDF, while the kitot konenutare not. The distinction between the kitot konenut and the area hagmar is merely a technical one, with the same settlers often serving in both units.

In short, the settlement appoints a security coordinator who essentially commands his own volunteer militia that is armed and funded by the state. Those same settler volunteers also often serve in uniformed army reservist militias under the control of the military that coordinates with their settlement. The volunteer militias, the reservist militias, and the military itself all work together to attack and terrorize Palestinians in the West Bank.

Graphic credit: Meghnad Bose

Although wartime command is meant to shift from local coordinators to the army, the West Bank has never officially been declared a war zone. It remains under what the military calls “ongoing routine security,” a permanent state of civilian control by armed settlers under military cover.

“On paper, the weapons are checked in and out by the ravshatz, but in reality, they almost never come back,” said an Israeli solidarity activist who monitors settler violence in the South Hebron Hills, and who spoke to Drop Site on condition of anonymity, citing security concerns. “In some councils, the armory rules are strict; in others, people just keep the guns at home. It depends on the local kabat and how much the army wants to look the other way.”

While the ravshatz and the settlement’s kitat konenut are technically limited to operating within their settlement, military auxiliaries like hagmar, operating in theory at broader territorial echelons, are not.

“The result is that we have settlers operating as the military without regulation,” Roni Peli, of Israeli human rights organization Yesh Din, told Drop Site.

Drop Site News is reader-supported. Consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Forced Evictions

This system was on full display in mid-October on the outskirts of Al-Mufaqara, a hamlet in Masafer Yatta. Armed settlers broke into a Palestinian family’s cave-home, forcibly expelled them, and moved in—threatening to shoot anyone who approached. I arrived a few hours later to find the family and several Israeli solidarity activists outside waiting for the police.

“When the Palestinians tried to stop them, a group of armed men arrived, some in uniform, some not, including Binyamin Zarbiv, the ravshatz from Ma’on,” an Israeli activist who witnessed the incident told Drop Site, pointing to the settlement some 200 meters away. They also spoke on the condition of anonymity, citing security concerns. “They aimed their rifles at the Palestinians and at us, while the settlers carried their belongings inside.”

As we waited, an armed man in a ragtag uniform, identified by the activist as one of those who had arrived earlier, demanded my ID. He claimed to be representing Hagmar Har Hevron, though no such Israeli military unit officially exists, and identified himself as a member of three bodies: Ma’on’s rapid-response squad, the area hagmar unit, and a so-called farm patrol. He refused to say which group had sent him.

“The settler who broke in called the ravshatz on his phone,” the activist said. “That’s how it usually happens. The ravshatz makes a few calls, and within minutes they start showing up—half in uniform, half not—all with state-issued rifles.”

The man told me that he would be collecting a full day’s pay for his work, and acknowledged that he could do so whenever he wanted. He claimed his rifle came “from the army,” adding that he had received it “from the base,” but when pressed, he clarified that the “base” was the settlement itself, where no army base exists.

When the Israeli Civil Administration and police finally arrived, accompanied by army soldiers, they declined to review documents proving Palestinian ownership and left the militia in control of the site.

A few kilometers away in Susya, footage from August 24 shows a group of armed men invading the small community, some in fatigues, others in civilian clothes. One of them assaulted a Palestinian resident who was later hospitalized with a severe concussion.

(Footage from Susya on August 24, 2025. courtesy of David Schutz)

The head of the Susya village council, Jihad Nawaja, said he recognized the attackers immediately. “I’ve known this man for 15 years,” Nawaja told Drop Site, pointing to an armed settler wearing civilian clothing. “The one who beat the Palestinian was his son. They came with armed men from Susya, in uniform, to tell us to evacuate. ‘Leave and move to Hebron,’ they said. There was no other reason for them to come that night.”

Nawaja’s brother, B’Tselem researcher Nasser Nawaja, who is also a resident of Susya, said armed groups of organized settlers frequently also detain Palestinians. They “kidnap people often … anyone who tries to resist eviction. They take him, warn him not to do it again, and release him later,” he said. “I once saw them during an attack near Susya. Settlers were escaping from the police, and one of these men helped drive them away.”

In a recurring pattern, settlers raid in broad daylight and, hours later, the same men reappear in uniform to enforce closures and secure the ground they seized.

“They also actively intercept the army’s radio frequency, to listen in on coordinations with the Palestinians. Once we had coordination for plowing, from four to eight o’clock… they found out and made sure it stopped,” Nawaja added.

Rights groups report that complaints about organized violence by armed settlers routinely bounce between various jurisdictions of Israeli authorities. Police classify suspects as “military auxiliaries” and pass the files to the army; the army returns them as “civilian” cases; civilian authorities cite military jurisdiction, and the investigations close for “lack of evidence.”

A Private Army

Before October 7, 2023, Israel maintained about 450 rapid response squads, according to a 2024 report by the Knesset Research and Information Center (KRIC)—the non-partisan research arm of the Israeli parliament. Roughly 390 of the kitot konenut operated under army supervision in West Bank settlements, while the border police (a police paramilitary unit that operates on both sides of the green line) oversaw 50 and the police oversaw fewer than ten.

The report found that the division of control between government bodies over these units rests on a 1974 government decision that was never published and is missing from the state archives. Military Order 432 of 1971, which regulates kitot konenut in the West Bank, and related directives on open fire and emergency mobilization also remain classified.

In the report, researchers described sweeping non-cooperation from the Israel police, Defense Ministry, and IDF—none of which provided data on the squads’ authority, arming, or oversight. The KRIC noted that its report relied on partial replies and public sources, as “no response was received from the bodies involved.”

Following October 7, National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir announced more than 700 new kitot konenut, expanding the police-run network, while the army’s share remained largely unchanged. The new units were incorporated under the border police, the only way Ben-Gvir could get a mandate to operate outside the green line. By early 2024, the government listed 906 active units, with a target of 1,086 by year’s end. By late October 2025, 1,052 kitot konenut units were active.

In October 2023, Ben-Gvir’s ministry also began distributing around 10,000 newly purchased assault rifles to kitot konenut and loosened gun-ownership eligibility, while the Defense Ministry supplied training, ammunition, and armory infrastructure. By November 2025, Ben-Gvir’s office said roughly 230,000 gun licenses had been issued over the past two years. Meanwhile, the National Missions Ministry funded vehicles, drones, and surveillance systems; regional councils added weapons and vehicles through private and foreign donors, including U.S.-Jewish federations that gifted sniper rifles to kitot konenut under campaigns like “Friends of Samaria.”

The KRIC noted that much of this equipment was distributed through ravshatz-operated armories, bypassing Israeli military depots. Earlier in 2023, the government created the Mishmar Leumi (National Guard), a Border Police reserve under Ben-Gvir, meant to absorb local militias and volunteer frameworks. Activated after October 7, it became a vehicle for mobilizing and reinforcing kitot konenut, with recruitment tracks allowing civilians to join armed policing roles outside the traditional Magav or IDF pathways. Formally under the police commissioner, its control can shift to the minister of national security in emergencies.Leading critics call it Ben-Gvir’s “private army.”

Simultaneously, the army expanded hagmar battalions, adding about 5,500 reservists for a total of roughly 8,000, divided between regional companies and settlement-level auxiliaries known as bnei hayishuv (“sons of the town”).

Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich’s new Settlements Administration inside the Defense Ministry absorbed powers from the Civil Administration, giving his office direct control over civilian-security budgets: armories, budget lines, weapons requests, and patrol mandates. Under this structure, new siyur havot (“farm patrols”) emerged to police land outside settlement boundaries, funded from the same Defense Ministry budgets as the kitot konenut.

By May 2024, when the army began reducinghagmar deployments, a parallel militia network aligned to Ben-Gvir’s National Guard and Smotrich’s policy priorities was already firmly entrenched. The military is now considering further troop reductions in the West Bank, transferring security responsibilities to “local elements,” according to the Jerusalem Post.

On their websites, West Bank regional councils describe their roles in deliberately opaque terms: the South Hebron Hills Council boasts of “creating and maintaining local security elements”; the Jordan Valley Council pledges to “define security components in conjunction with security forces”; and the Binyamin Council vows to “improve and maintain local security components.”

“They don’t distinguish even between the hagmar and the rapid-response squads, everyone’s in uniform now,” a resident from the South Hebron Hills told Drop Site on condition of anonymity. “I know many of them by name. Some even have criminal records. Now they’ve been given uniforms.”

This article is published in collaboration with Egab.

From Drop Site News via This RSS Feed.