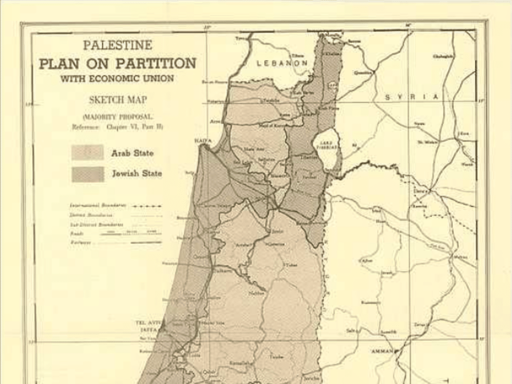

The boundary separating Lebanon and Palestine today wasn’t a random accident.

It was shaped by European colonial powers, you guessed it Britain and France, with little regard for the people it would impact. What they saw as a “backward” border would later fuel Zionist expansion into the Galilee and Israel’s multiple incursions into Lebanon.

As a Lebanese subject opposed to Zionism and committed to resistance, I cannot view this history as detached. The line drawn in the sand in 1923 was the start of a century-long struggle of fragmentation, dispossession, and resistance. This struggle still echoes in the lives of millions today.

Severing economic lifelines

Regions that once formed a single economic unit were sliced in half like an experimental collage—torn apart and reassembled. This was done with no regard for the local trade networks and lives they disrupted.

The regions of Marj‘Ayoun and the Hula Valley illustrate this violent separation.

Marj‘Ayoun, home to landowners, mill operators, and grain merchants, became part of Lebanon and the Hula Valley was assigned to Palestine.

The division impoverished the region. Its inhabitants fled outwards as their economic lifeblood dried up. In subsequent years, after the establishment of the Israel colonial-settler state, Kiryat Shmona, an Israeli town, would emerge as the new economic hub of the Galilee.

The town of Bint Jbeil is another casualty of colonial partition. It had historically connected key cities across Lebanon and Palestine — Tyre with Acre, Safad, and the Hula Basin — while facilitating the flow of goods and people. The boundary drawn by the British diminished these exchanges and mobility. It also stunted future economic prospects for agricultural communities.

The rural communities lost the mobility they depended upon. They could no longer graze livestock in adjacent valleys, sell crops in neighbouring towns, or undertake odd-jobs for additional income. As livings standards declined people migrated to distant cities. The Lebanese south predominantly home to Lebanon’s Shiite community and long neglected by the Lebanese capital had no alternative economic lifeline.

For its inhabitants, access to the markets of northern Palestine was essential for its survival.

These boundaries were not drawn arbitrarily but deliberately. They laid down the groundwork for future domination.

Policing a fragile frontier

Still, locals, especially farmers, repeatedly defied the new boundary — and not always intentionally. It wasn’t, after all, ironclad — an idea Israel would eventually execute through its unlawful partition wall in the occupied West Bank.

Fearful of Arab communities rising-up to express their dismay, British and French officials hatched a plan to regulate cross-border movement.

In 1926 an agreement was signed in Jerusalem giving them administrative powers to police the porous frontier. Residents from Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria would cross without passports and transport livestock, tools, and agricultural produce without customs duties.

This was no act of generosity but an admission that people’s old ways of living, fractured by the colonial boundary, needed to be restored, albeit under a colonial guise.

For Lebanon’s southern community, they turned their sights to northern Palestine — a critical lifeline at the time.

Some sought employment opportunities, while others turned to cross-border smuggling of hashish, weapons, and produce. At times, even Jewish migrants were smuggled illegally into Palestine. Goods produced in Jewish settlements were sold into Lebanon and Syria. People abandoned by their state had no choice but to adapt.

The enduring wounds of partition in Southern Lebanon

The 1926 agreement wasn’t long lasting either, terminated after the 1948 Arab–Israeli war.

Israel refused to recognise any treaty the British has signed into existence and the closure of the border dealt a fatal blow to the South of Lebanon.

On the occupied side, Arab villages were emptied and repopulated by Jewish settlers. These settlers had no interest in maintaining economic ties with their Lebanese neighbours. On the Lebanese side, economic isolation deepened.

Beirut’s political elite—many of whom believed Israel might one day annex the region—saw little incentive to invest in the Shiite-majority south.

By the late 1960s, the frontier turned into a battleground between Palestinian fighters and Israeli forces.

The presence of Palestinian guerrillas and recurring Israeli raids served as a convenient excuse for the Lebanese state to side step is welfare duties towards communities along the frontier.

The deeper truth was the structural marginalisation of a population. They had the least representation in the halls of power.

Mounting poverty, displacement, and devastation endured by South Lebanon, exacerbated by unending Israeli assaults (until this present day), can be directly traced to the Franco–British partition of in the 1920s.

A colonial line, drawn with arrogant indifference, divided communities and shaped the conditions that later enabled both occupation and resistance.

Featured image via National Library of Israel

From Canary via This RSS Feed.